This is the first part of a three-part version of the “Best Inventions of All Time” list arranged chronologically. These lists are much longer than the one arranged by rank, which only includes inventions found on 4 or more of the 21 original source lists. The chronological lists contain every invention that was on at least two of the “Best Inventions” lists I found. This version of the list also contains much more information about the invention, including precursors, improvements and further developments. Most inventions are not the product of one human mind but many, and the person named “inventor” is usually one link in a chain that extends backward and forward in time.

For Part 2 of the list (1800-1899), go here.

For Part 3 of the list (1900-Present), go here.

STONE TOOLS – c. 2.6 million years ago (mya) – Ethiopia

The first stone tools used by ancestors of modern humans were made 2.6 million years ago (mya), in Ethiopia and are categorized as Oldowan tools. The toolmakers took core rocks or pebbles and struck them with a spherical hammerstone, creating conchoidal fractures that often made an edge or sharp tip and left behind flakes. The earliest tools of the next period, the Acheulean, lasting from 1.7 mya to 300,000 BCE, are found in Kenya. These more complex tools include biface stones, which were worked extensively on both faces, and include the first hand axes. In many areas, the next phase was the Mousterian, which lasted from 300,000 BCE to 28,000 BCE and produced smaller and sharper knife-like tools and scrapers. In Europe, these mostly flint tools were identified with the Neanderthals. In some areas, man developed tools that define the fourth, or Aurignacian, phase, which lasted from 43,000 BCE to 33,000 BCE in parts of Europe and Asia. The tools are characterized by blades, instead of flakes from prepared cores. Phase five is the Microlithic, characterized by the first multi-part, or composite tools, such as those fastened to a stone or wooden haft. It lasted from 15,000 BCE to 10,000 BCE. The last phase, the Neolithic, extended from 10,000 BCE to between 4500 and 2000 BCE. Neolithic toolmaking is characterized by ground or polished implements made of non-flaking materials. During this phase, polished stone axes were used to clear forests in temperate zones.

A stone tool from the Olduvan period.

SPOKEN LANGUAGE – c. 1.8 mya-100,000 BCE – Africa

The timing and mechanism for the development of human speech and language are the subject of vigorous debate in the scientific community, with no consensus of opinion. Most agree that our speech organs evolved for feeding and breathing, not speech, but that our tongue, lips, larynx, hyoid bone and respiratory apparatus were fortuitously well-designed to produce speech. Theories about the origins of speech and language abound. Continuity theorists believe in a long, slow evolution of human language from the pre-language systems of our primate ancestors. Some continuity scientists believe that the first language used only gestures and that speech came later, as a supplement. Discontinuity theory holds that human language is so unusual that it can only be explained if it evolved quickly due to a genetic basis. Linguist Noam Chomsky, a prominent discontinuity theorist, believes that there are basic, universal speech components that underlie all language and explain both the uniqueness of human language and certain common features of all languages.

As the shape of the human larynx evolved, speech as we know it became physically possible.

FIRE – 400,000 BCE – Africa

Fire provided early humans with a source of light and warmth, protection from pests and predators and the ability to cook food. Because fire naturally occurs through lightning strikes, it can be difficult to distinguish between man-made and natural fire in the archaeological record. There is some evidence of that humans used and controlled fire as far back as 1.9 mya, while artifacts from various archeological sites give a range of dates: 1.7 mya (Yuanmou, China); 1.5 mya (Koobi Fora, Kenya); 1.42 mya (Chesowanja, Kenya); 1.0 mya (Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa); and 830,000-500,000 BCE (Trinil, Indonesia). Despite these tantalizing discoveries, many scholars believe that man (specifically Homo erectus) did not master the controlled use of fire until about 400,000 BCE, based on well-preserved evidence from sites in South Africa.

The Zhoukoudian Caves in China provide some of the earliest evidence of human control of fire, with dates between 460,000 BCE and 230,000 BCE.

COOKING – 250,000 BCE – Africa, Europe, Middle East

The date that humans began cooking food is the subject of much debate. One group of scientists believes that cooking was invented between 2.3 and 1.8 mya. Other researchers posit a much more recent date: between 38,000 BCE and 8000 BCE. A majority of anthropologists believe that cooking began about 250,000 BCE, when evidence of hearths began appearing in human settlements in Africa, Europe and the Middle East.

Layer of successive hearths from Kebara Cave in Israel, dating to 58,000 to 46,000 BCE.

POTTERY – 20,000 BCE – China

Pottery is defined by some as any fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, while some archaeologists restrict pottery to ceramic vessels. A ceramic figurine from the Czech Republic dates to 29,000-25,000 BCE, but the first pottery vessels were found in China and date to 20,000 BCE. Pottery was found in the Russian Far East from 14,000 BCE and in Japan from 10,500 BCE. The potter’s wheel, which revolutionized pottery making, was invented in Mesopotamia between 6000 and 4000 BCE.

Pottery dating to 20,000 BCE from Zianrendong Cave, China.

AGRICULTURE – 11,000 BCE – Syria, Greece

The move from hunter-gatherer to agriculture was gradual and occurred at different times in different places. Evidence of humans exerting some control over wild grain is found in Israel in 20,000 BCE. There is evidence of planned cultivation and trait selection of rye at a Syrian site dating to 11,000 BCE. At about the same time, domesticated lentils, vetch, pistchios and almonds were found in Franchthi Cave in Greece. The eight founder crops of agriculture (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chickpeas and flax) were domesticated some time after 9500 BCE at various sites in the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Cyprus and part of Turkey). The oldest known agricultural settlement is in Cyprus, dating from 9100-8600 BCE. Rice and millet were domesticated in China by 8000 BCE. Farming was fully established along the Nile River by 8000 BCE (although there is some evidence of agriculture in Egypt as early as 10,000 BCE) and in Mesopotamia by 7000 BCE. The first evidence of agriculture in the Indus Valley dates from 7000-6000 BCE. The first signs of agriculture in the Iberian peninsula date from 6000-4500 BCE. The oldest field systems, including stone walls, are found in Ireland and date to 5500 BCE. By 5500 BCE, the Sumerians had developed large-scale intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping, organized irrigation and use of a specialized labor force. By 5000 BCE, humans in Africa’s Sahel region had domesticated rice and sorghum. Maize was domesticated in Mesoamerica around 3000-2700 BCE.

A Sumerian clay harvesting sickle dating from 3000 BCE.

BOW AND ARROW – 9000 BCE – Denmark

The bow and arrow gradually replaced the earlier spear-thrower and spear as a weapon in all continents except Australia. There is evidence of stone arrowheads going back as far as 69,000 BCE in Africa, and depictions of men using the bow and arrow in cave paintings from 20,000 BCE at Valltorta Gorge, in Spain. The oldest existing bows, the Holmegaard bows, were found in a bog in Denmark. They are made of elm wood and date to 9000 BCE. There is also evidence of pine-shafted arrows designed for use with bows and flint points at Stellmoor, Germany, dating from 8000 BCE. Bows made of yew wood dating to 5400-5200 BCE were found in Catalonia.

One of the wooden Holmegaard bows, which dates to 9000 BCE.

WINE – 6000 BCE – Georgia

Wild grapes grow in Georgia, the Levant, Turkey, Iran and Armenia, but it is not clear where winemaking first developed. Patrick McGovern argues for the Georgian origin of wine in his book, Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003). The earliest winemaking sites discovered have been in Georgia, dating to 6000 BCE, and Iran, dating to 5000 BCE. Evidence of winemaking in Macedonia dates to 4500 BCE. Remains of a winery found in an Armenian cave from 4100 BCE includes a wine press, fermentation vats, jars and cups, as well as seeds and vines. Domesticated grapes and winemaking are evident in Sumer and Egypt beginning in 3200 BCE. Winemakers in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome advanced the technology of the craft significantly.

Archaeologists excavated this winemaking facility in Armenia, dating to 4100 BCE.

BEER – 5000 BCE – Iran

Chemical tests of pottery jars from Iran indicate that beer was produced as early as 5000 BCE. There is evidence of beer in Mesopotamia from 4000 BCE. Egyptian pharoahs drank beer in 3000 BCE. In the Middle Ages, the commercial distribution of beer was aided by Catholic monks, who made and sold beer from their monasteries. The first mention of using hops to make beer comes from a Carolingian abbot in 822 CE. Most beer was top-fermented during its early history. Bottom-fermenting was discovered by accident in the 16th Century and has since become the most common method. Brewing became an industrial process in the mid-18th Century, with the introduction of the steam engine, the thermometer and the hydrometer.

Mesopotamian brewing instructions from 3100 BCE.

WOVEN CLOTH – 5000 BCE – Egypt

In 2009, scientists announced that they had found the oldest woven cloth: twisted fibers of flax, some of them dyed, found in a cave in Georgia and dating to 36,000-30,000 BCE. Impressions of woven cloth found on a clay surface from Moravia in the Czech Republic date to 26,000 BCE. In 1993, archaeologists found woven linen cloth dating to 7000 BCE wrapped around an axe handle at a site in Turkey. Woven flax cloth dating to 5000 BCE was found in Egypt. It was made using a plain weave, 12 threads by 9 threads per centimeter. By 2000 BCE, most cultures were using wool as the primary fiber for weaving. By 700 CE, weavers were using horizontal and vertical looms in Asia, Africa and Europe. At some point after 700 CE, Islamic civilizations invented the pit-treadle loom, which was soon found in Syria, Iran and East Africa. Christian weavers adopted the pit-treadle loom via Moorish Spain after 1177 and it soon became the standard. During the Middle Ages, weavers began using cotton and silk fibers to make cloth. In the 18th Century, weaving, which had been a cottage industry, became industrialized. John Kay (UK) invented the flying shuttle in 1733. James Hargreaves (UK) invented the spinning jenny in 1764 and Samuel Crompton (UK) invented the spinning mule between 1775-1779. Power weaving started (fitfully) with the work of Edmund Cartwright (UK) in 1785, but the first semiautomatic loom wasn’t introduced until 1842. The Jacquard loom, invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard (France) in 1801, simplified the process of weaving of complicated patterns.

Microscopic photos of woven flax fibers found in a Georgia cave and dating to 36,000-30,000 BCE.

Egyptian linen, woven in 5000 BCE.

ROWING OARS – 5000-4500 BCE – China

The earliest evidence of oars for rowing boats comes from the Hemudu Culture in China. Wooden oars dating from 5000-4500 BCE were found in Yuyao, Zhejiang, where scientists also found pottery vessels in the shape of canoes. A two-foot long oar dating from 4000 BCE was found in Ishikawa Prefecture in Japan. Ships propelled by rows of oarsmen dominated the early world, beginning with the Phoenician galley, first invented about 1100 BCE. By 700 BCE, the Phoenicians had created the bireme, with two banks of oarsmen, one above the other. By the mid-5th Century BCE, both the Greek and Persian fleets contained numerous triremes, with three banks of oarsmen. In 260 BCE, the Carthaginians were using quinqueremes, with five banks of oarsmen, for a total of 300 oars. Europeans followed a similar path – Germanic tribes used boats with oars and sails beginning in the 5th Century CE, including the Viking ships and later the Normans in the 11th Century.

This wooden oar dating to 5000 BCE was found in South Korea.

IRON WORKING – 5000-4000 BCE – Iran

Iron, a common element in the earth’s crust and in meteorites, is easily corroded, so few ancient iron artifacts remain. The earliest man-made iron objects that still exist were found in Iran and date to 5000-4000 BCE. They were made from iron-nickel meteorites, as were the earliest iron artifacts from Egypt and Mesopotamia, dating from 4000-3000 BCE, and China, from 2000-1000 BCE. There is early evidence of smelting of native iron ore to create the first wrought iron in Mesopotamia and Syria about 3000-2700 BCE and India in 1800-1200 BCE. The Hittites, in Anatolia (now Turkey), devoted significant resources to iron working in bellows-aided furnaces called bloomeries, starting in 1500-1200 BCE (although Hittite iron artifacts as old as 2500 BCE exist). Around 1500 BCE, smelted iron objects appear more frequently in Mesopotamia, Egypt and Niger as well. By 1100-1000 BCE, making wrought iron by smelting iron ores had spread around the world from sub-Saharan Africa to China to Greece, ushering in the Iron Age. Wrought ironworking reached central Europe in the 8th Century BCE and became common in Northern Europe and Britain after 500 BCE. Meanwhile, Chinese ironworkers first produced cast iron, which was cheaper to produce than wrought iron, in the 5th Century BCE. A major improvement in technique for making wrought iron was introduced by Henry Cort (UK) in 1783, when he invented the puddling process for refining iron ore. Cast iron production reached Europe in the Middle Ages. Abraham Darby (UK) built a coke-fired blast furnace in 1709 to make cast iron more efficiently.

These remains of an early bloomery iron smelting operations, located at Tell Hammeh in Jordan date to about 1150 BCE.

SAILBOAT – 5500-5000 BCE – Mesopotamia

The earliest evidence of sailing boats is an image on an artifact found in Kuwait dating to between 5500-5000 BCE. By 3200 BCE, Sumerians in Mesopotamia were using square-rigged sailboats for trade. The Ancient Egyptians and the Phoenicians had significant knowledge of sail construction at least as far back as 3000 BCE. By 200 CE, Chinese boatbuilders were building multi-masted sailing junks that could carry 200 people.

A depiction of an Egyptian sailboat from about 1500 BCE.

WHEEL – 4000–3500 BCE – Mesopotamia, Indus Valley, Northern Caucasus; Central Europe

Civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe all invented wheeled vehicles between 4000 and 3500 BCE. The earliest clear depiction of a wheeled vehicle was found in Poland and dates to 3500-3350 BCE. The oldest surviving wheel was found in the Ljubljana Marshes in Slovenia and dates to approximately 3250 BCE. Wheeled vehicles are found in the Indus Valley by 3000-2000 BCE. The spoke-wheeled chariot was invented some time between 2200 and 1550 BCE, and reached China and Scandanavia by 1200 BCE. The earliest wheels were made of wood. Wire wheels and pneumatic tires were invented in the mid-19th Century.

The remains of the oldest existing wheel and axle, dating to 3250 BCE.

DOMESTICATION OF THE HORSE – 4000-3500 BCE – Ukraine/Kazakhstan

Horse domestication did not occur once, but many times. Modern geneticists trace the genetic make-up of the modern horse to 77 separate mares. Domestication probably first took place in the Eurasian steppes, particularly in what is now the Ukraine and Kazakhstan, between 4000 and 3500 BCE, although in Russia, there are horse bones and carved images of horses in graves dating to 4800-4400 BCE. Horses may have been kept as meat animals before being trained as working animals, but the Botai, of Kazakhstan, may have ridden domesticated horses to hunt wild horses as early as 3500-3000 BCE. Evidence of wear from bits dates from the same time. Evidence of domesticated horses was found in Hungary dating to 2500 BCE; in Mesopotamia from 2300 BCE; and in China from 2000 BCE. A Somali rock painting of a man on horseback dates to 3000-1000 BCE. The earliest evidence of horse-drawn chariots was found in Russia and Kazakhstan and dates from 2100-1700 BCE. By 1600 BCE, horse-drawn chariots are found in Greece, Egypt and Mesopotamia and by 1100 BCE in China. Mounted cavalry became a potent war weapon beginning in Mesopotamia between 1200 and 500 BCE, and then spread throughout the world.

This horse, which died in Russia in 1909, may have been the last individual related to the original wild horses, known as tarpans. No true tarpans survive today.

WRITING – 3200 BCE – Mesopotamia

Written language evolved from pictures and other symbols first into proto-writing, and then into true writing. Sumerian archaic cuneiform script was invented around 3200 BCE, although the first true written texts do not appear until about 2600 BCE. The first Egyptian hieroglyphics date to 3400-3200 BCE; the Indus script of Ancient India dates to 3200 BCE; and Chinese characters date to 1600-1200 BCE, but there is debate about whether these were independent discoveries or derived from pre-existing scripts. The Phoenicians began to develop the first phonetic writing system between 2000 and 1000 BCE. Mesoamerican cultures developed writing systems independently, with the Olmecs of Mexico the earliest, beginning about 900-600 BCE.

This is an example of Sumerian cuneiform script in about 2600 BCE.

NAILS – 3400 BCE – Egypt

The earliest nails, which were found in Egypt and date to 3400 BCE, were made of bronze. In the Iron Age, wrought-iron replaced bronze. The Romans were prolific users of iron nails. Nails were hand-wrought until the arrival of the cut nail in 1800, although the rise of the slitting mill in the late 16th Century reduced much of the manual effort in nail making. Machines for making cut nails faster and more consistently were patented by Jacob Perkins (US) in 1795 and Joseph Dyer (UK) and dominated the industry until 1860, with the arrival of the wire nail. The first wire nails came from France. By 1863, Belgian wire nails were a strong competitor. By 1875, Joseph Henry Nettlefold (UK) was producing wire nails in the UK. Producing wire nails was very cheap and required little human involvement and by the turn of the 20th Century, wire nails had triumphed over both cut and hand-wrought nails.

These wrought iron nails were found in Ancient Roman sites and date from between 50 BCE and 50 CE.

BRONZE – 3250 BCE – Mesopotamia

Bronze is an alloy of copper. The first bronze was made with copper mixed with arsenic in Mesopotamia about 3250 BCE. Some groups were switching to the superior copper/tin alloy as early as 3000 BCE: Susa (Iran), Luristan (Iran), Mesopotamia (Iraq), and China. Cultures in Northern Italy were using copper/arsenic bronze in 2800-2200 BCE. By 2000 BCE, the standard in Europe and Asia had become copper/tin, although copper/zinc was used in some areas. Tin and copper are rarely found together, so extensive trade was necessary to make bronze. As iron working became more sophisticated, iron gradually replaced bronze – it was more common and allowed more flexibility, although some continued to prize the harder bronze weapons. In Mesoamerica, Sican Culture in Peru was making both copper/arsenic and copper/tin bronze in 900-1350 CE.

Bronze deer from Bulgaria, dating from 900-600 BCE.

OX-DRAWN PLOW – 3000 BCE – Egypt

The earliest plow, the ard, dug a furrow in the earth for planting, but did not turn the soil over. Oxen and other draft animals pulled the plow across the fields. The first ards are found in Ancient Egypt around 3000 BCE, and shortly thereafter in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. The invention soon spread to other parts of Asia and Europe. The earliest improvement to the plow was the coulter, a blade-like component that cut an edge in front of the plowshare to create a smoothly cut bank.

This Egyptian painting shows a farmer plowing his field with an ard about 1200 BCE.

SOAP – 2800 BCE – Mesopotamia

To be effective at cleaning, soap requires fatty acids (from animal or vegetable oils) plus an alkali metal such as sodium or potassium. The earliest evidence of soap is from Mesopotamia in 2800 BCE. An Egyptian papyrus dating to 1550 BCE notes that the Ancient Egyptians bathed regularly. There are references to soap in Ancient Roman documents from the 1st Century CE. In the late 6th Century CE, soapmakers in Naples had formed a guild, and by the 8th Century CE, soap-making was well-known in Italy and Spain. Charlemagne’s 800 CE will mentions soap. A 12th Century Islamic document references alkali, derived from ashes, as a key soap ingredient. By the 13th Century, Islamic soap manufacturing had spread to Nablus, Fes, Damascus and Aleppo. By 1450, French soapmaking was concentrated in Provence. Finer soaps using vegetable oil were produced in Europe beginning in the 16th Century. Large scale soap manufacturing began in 1789 in London with Andrew Pears. The first soap powder was made by Robert Spear Hudson (UK) in 1837. William Shepphard patented liquid soap in 1865, and B.J. Johnson introduced Palmolive liquid soap in 1898.

This Egyptian papyrus from 1500 BCE describes the use of soap for washing.

ABACUS – 2700 BCE – Mesopotamia

The first evidence of use of an abacus counting tool is by the Sumerians about 2700 BCE. Abacus use spread to Ancient Egypt, Persia (600 BCE) and Ancient Greece (400 BCE). The oldest still-existing abacus was found on the Greek isle of Salamis and dates to 300 BCE. There is evidence of a Chinese abacus from the 2nd Century BCE. Ancient Romans used an abacus as far back as the 1st Century BCE. Indian sources refer to an abacus during the 1st Century CE. Pope Sylvester II, who served from 999-1003, brought Arabic numerals to Europe and reintroduced the Roman abacus, with improvements. The Chinese abacus migrated to Korea in 1400 and Japan in 1600. The Russian abacus was invented in the 17th Century.

An abacus from Ancient Rome, dating to about 200 CE.

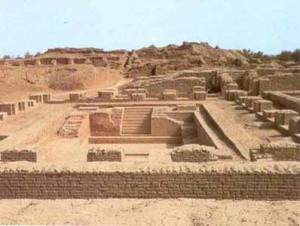

FLUSH TOILET – 2600 BCE – Indus Valley, Pakistan

The Indus Valley Civilization, in modern-day Pakistan, had an elaborate plumbing system as far back as 2600 BCE. Almost every house in the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro had a flush toilet, which was attached to a sophisticated sewage system. The Indus Valley Civilization collapsed due to invaders in about 1700 BCE. Flush toilets were later used in Minoan Crete (1800 BCE) and Minoan Akrotiri (1500 BCE), Bahrain (900 BCE) and the Roman Empire (1-400 CE).

Excavation of the Indus Valley civilization in what is now Pakistan. Every home had a flush toilet.

GLASS – 2500 BCE – Syria, Mesopotamia or Ancient Egypt

The first glass may have been produced as an accidental byproduct of metal-working. The earliest glass beads are found in Syria, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, dating to 2500 BCE. Glassmaking began in South Asia in 1730 BCE. Glassmaking increased significantly in Ancient Egypt and Syria in the late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BCE). By the 15th Century BCE, glass production is found in Western Asia, Crete, Egypt and Mycenaean Greece. Colorless glass is first found in the 9th Century BCE in Syria and Cyprus. China began making glass around 300 BCE. Glass blowing was first discovered on the Syro-Judean coast in the 1st Century BCE, a finding that made glass much less expensive to make. Alexandrian glass blowers learned to make clear glass around 100 CE, which allowed for the first glass windows.

This glass jar was made in Ancient Egypt between 1539 and 1295 BCE (18th Dynasty; New Kingdom).

STEEL – 2000 BCE – Anatolia (Turkey)

Steel is an alloy of iron mixed with carbon. It was probably first produced by accident when forgers, seeking to make an iron implement stronger, added progressively more carbon. Early steel was made in a bloomery, and, much later, the puddling furnace. The oldest known steel artifact comes from a site in Turkey and dates to 2000 BCE. Blacksmiths in Luristan (present-day Iran) were making steel by 1000 BCE. High-quality Wootz steel was invented in India around 300 BCE using the crucible steel method; it eventually traveled to the Middle East beginning in 300 CE, where it was known as Damascus steel. The Roman Army used weapons made of Noric steel starting about 100 BCE. Between the 1st and 4th centuries, the Haya in what is now Tanzania, developed a highly sophisticated steel-making process. In the 17th Century, improvements were made to the steelmaking process. Because steelmaking was difficult and expensive, it was used only for cutlery and weaponry until the 1850s, when Henry Bessemer’s process made mass production feasible.

Steel dagger from the Iberian Peninsula, dating to between 450 and 200 BCE.

LOCK AND KEY – 2000 BCE – Egypt

The Egyptians developed the wooden pin lock about 2000 BCE. A simple version of the pin tumbler lock was installed in the palace of Assyrian King Sargon II at Khorsabad (Iraq) in the late 8th Century BCE. In 700 BCE, the Greeks invented a lock and key that required the first keyhole. The Romans invented the warded lock between 100 BCE and 100 CE. The first all-metal lock dates to 870-900 CE, in the UK. A lever tumbler lock was developed by Robert Barron (UK) in 1778 and then improved by Jeremiah Chubb in 1818. An alternative lock design using a circular key was invented by Joseph Bramah in 1784. The first double-acting pin tumbler lock was patented by Abraham Stansbury (US/UK) in 1805, but the modern version was created by Linus Yale, Sr. (US) in 1848 and improved by his son, Linus Yale, Jr. (US) in 1861.

Vikings who settled in York, UK made this lock and keys between 850 and 950 CE.

ALPHABET – 1700–1500 BCE – Phoenicia

The Phoenician alphabet, which had no vowels, was the precursor to many of the writing systems in use today and throughout history. It led directly to Aramaic, which led to Arabic and Hebrew. The Greeks converted certain Phoenician letters to vowels, and the resulting language became the basis for Latin, Cyrillic and Coptic scripts.

These gold tablets, which date from 500 BCE, contain Phoenician (on left) and Etruscan writing.

UMBRELLA – 700 BCE – Assyria

The first umbrellas were used to protect people from the sun. At the ruins of the city of Nineveh, an umbrella is depicted in a 700 BCE bas relief protecting the head of Assyrian King Ashurbanipal. Similar sculptures are found at Persepolis in Persia (now Iran). The umbrella, or parasol, was a female fashion accessory in Greece of the 5th Century BCE and later in Ancient Rome. The first reference to a collapsible umbrella comes from China in 21 CE. A collapsible umbrella was discovered in a 1st Century CE tomb in Korea. A 2nd Century CE Chinese commentator refers to an umbrella with bendable joints allowing it to be extended or retracted. Umbrellas are known in India from the 4th Century CE. It was not until the mid-17th Century that people in France and England began to use umbrellas, probably adopted from China. The modern steel-ribbed umbrella first appeared in the 1780s in the UK.

This bas relief from 700 BCE depicts Assyrian King Ashurbanipal under an umbrella.

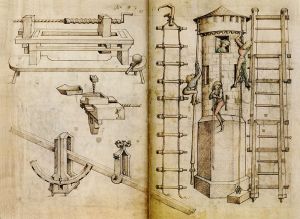

ARCHIMEDES’ SCREW – 700 BCE – Assyria

The Archimedes Screw brings water from a lower to a higher altitude and was an essential element of early irrigation. The first such screws are found in Assyria in 700 BCE, and therefore long predate their Archimedes of Syracuse, who lived from 287-212 BCE, to whom the invention is traditionally attributed. In 1405, German engineer Konrad Kyeser improved the design by adding a crank mechanism. The Archimedes Screw is still used today, often powered by electricity, to move water, sludge, grain and other liquid and solid materials.

This painting shows what using an Archimedes’ screw for irrigation might have been like.

Modern day Archimedes’ screws operating at Sea World in San Diego, California.

CROSSBOW – 600-500 BCE – China

Crossbows were first used in China as weapons of war between 600 and 500 BCE. Greek soldiers began using crossbows between 500-400 BCE. Romans used crossbows in war and hunting between 50 and 150 CE. There is evidence of crossbow use in Scotland between the 6th and 9th Centuries CE. The invention of pushlever and ratchet drawing mechanisms in the Middle Ages allowed the use of crossbows on horseback. The Saracens invented composite bows, made from layers of different material, and the Crusaders adopted the design upon their return to Europe. By 1525, the military crossbow had mostly been replaced by firearms.

This is a reconstruction of a Greek crossbow, or gastraphetes.

MOLDBOARD PLOW – 500 BCE – China

The moldboard plow, which is first found in China around 500 BCE, was a major advance in agriculture. The moldboard is a piece attached to the plow that turns over the soil, allowing nutrients to be brought to the surface. Instead of merely digging a furrow to plant seeds, the plow now added to the productivity of the soil. The invention spread all over the world and farmers experimented with the best shape for the moldboard. Moldboards were first seen in the UK in the late 6th Century CE. Thomas Jefferson (US) designed and built a modified moldboard for his plows in 1794.

This display shows a wooden plow taken apart to show the colter, share and moldboard.

CATAPULT – c. 425 BCE – Ancient Greece

The first catapults, which were invented in Greece about 425 BCE, were used to fire arrows with more power than a regular bow or crossbow and resembled a giant slingshot. Roman armies used catapults called arcuballista in the 3rd and 2nd Centuries BCE. During the Middle Ages, with the rise of castles and fortifications, the catapult became a powerful siege weapon. The Viking siege of Paris in 885-886 CE involved catapults on both sides. Among the types of medieval catapults were: the ballista, the springald, the mangonel, the onager, the trebuchet, and the couillard. Catapults were used to throw grenades in World War I and are still used on ships.

The remains of a ballista-type catapult found in Spain, dating to 400-200 BCE.

WHEELBARROW – 408–406 BCE – Attica, Ancient Greece

A single reference to a “one wheeler” on an inventory from Ancient Greece is the basis for some archeologists’ belief that wheelbarrows existed there shortly prior to 400 BCE. But the absence of any other evidence of wheelbarrows in Europe until at least 1000 years later leads others to say that the ‘one wheeler’, whatever it was, was not a wheelbarrow. On the other hand, there is significant evidence of wheelbarrows in China, including pictures, starting in 100-200 CE, with some references as early as 30 BCE. The earliest Chinese wheelbarrows had their wheels in front; after 300 BCE, most had a large centrally mounted wheel. Front-wheeled wheelbarrows are found in Medieval Europe between 1170 and 1250. The vehicle was restricted to England, France and the Low Countries until the 15th Century. James Dyson invented the Ballbarrow, with a ball instead of a wheel, in the 1970s. Honda introduced an electric wheelbarrow, the HPE60, in 1998.

This Chinese tomb mural from 100-200 CE clearly depicts someone using a wheelbarrow (left).

WATERMILL – 300-200 BCE – Ancient Greece

A watermill is a structure that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour, lumber or textile production, or metal shaping (rolling, grinding or wire drawing). The first water-driven wheel is the Perachora in Ancient Greece, dating to the 3rd Century BCE. The first horizontal-wheeled mill was made at the Greek colony of Byzantium between 250 and 200 BCE; while the first vertical-wheeled mill was made in Alexandria around 240 BCE. A water-powered grain mill existed in Asia Minor before 71 BCE. A Roman engineer described a watermill with an undershot wheel and a gearing mechanism between 40 and 10 BCE. Antipater described an overshot wheel watermill between 20 BCE and 10 CE. A 1st Century multiple mill complex in southern France had 16 overshot waterwheels and processed 4.5 tons of flour a day. A breastshot wheel mill from France dates to the late 2nd Century CE. A water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, dated to the 3rd Century CE, is the earliest to include a crank and connecting rod mechanism. The earliest known water-powered marble saws, located in Germany, are referenced in a 4th Century CE poem. The earliest known turbine mill was located in Roman North Africa and dates to the late 3rd-early 4th Century CE. India received watermills from the Romans in the early 4th Century CE. Waterwheels are found in China from 30 CE but there is no solid evidence for watermills until 488 CE. Ship mills and tide mills were introduced in the 6th Century CE. Japan obtained its first watermill in 610-670 CE and Tibet had one by 641 CE. The Islamic world obtained the technology from the Byzantine Empire; the earliest watermills in the Muslim world are from the 7th Century.

This watermill at Braine-le-Château, Belgium, dates from the 12th Century.

LOCK – 285-273 BCE – Egypt

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels. Before the invention of locks, people built dams to raise the water level. The most primitive lock is the flash lock, whereby a small gate in a dam can be opened and closed quickly to raise or lower the water level. The problem was that the flood of water often sank the boats. The next development was the staunch, or water gate, which held the water back. The first true lock was a type of water gate built in the Canal of the Pharaohs (the predecessor to the Suez Canal), under Egyptian King Ptolemy II between 285 and 273 BCE to handle the large difference in water level between the Nile and the Red Sea. (The Egyptians had begun a canal linking the Nile and the Mediterranean via the Red Sea in 2000 BCE, which was rebuilt by the Persians in 520-510 BCE under Darius I.) The next logical development after the water gate was the pound lock, with a chamber and gates at both ends, which was pioneered by Chinese engineer Qiao Weiyou in 984 CE. Perhaps the first European pound lock for multiple ships was built at Vreeswijk in The Netherlands in 1373; a single-ship pound lock was built near Bruges in 1396. The mitre lock, whose gates formed a V when closed, was an improvement on the pound lock. The invention is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci in the 1480s. A drawback of the pound lock was the enormous amount of water released with each ship, so that water supplies often had to be replenished through design (such as making sure a canal had a reservoir at its highest point), pumping, or water saving basins. Various engineering innovations have been used to make locks work more efficiently, such as inclined planes, marine railways, boat lifts, caisson locks, hydro-pneumatic lifts and diagonal locks.

The Négra lock, on France’s Canal du Midi, is a pound lock built in 1670.

MAGNETIC COMPASS – 206 BCE (Han Dynasty) – China

Magnetic compasses were invented after humans discovered that iron could be magnetized by contact with lodestone and once magnetized, would always point north. There is some evidence that the Olmecs, in present-day Mexico, used compasses for geomancy (a type of divination) between 1400-1000 BCE. The first confirmed compasses, made in China about 206 BCE, were not used for navigation, but divination and geomancy, and used a lodestone or magnetized ladle. The first recorded use of a compass for navigation is 1040-1044 CE, but possibly as early as 850 CE, in China; 1187-1202 in Western Europe and 1232 in Persia. Later (by 1088 in China), iron needles that had been magnetized by a lodestone replaced the lodestone or other large object as directional arm of the compass. In many early compasses, the iron needle would float in water. The first dry needle compasses are described in Chinese documents dating from 1100-1250. Another form of dry compass, the dry mariner’s compass, was invented in Europe around 1300, possibly by Flavio Gioja (Italy). Further developments included the bearing compass and surveyor’s compass (early 18th Century); the prismatic compass (1885); the Bézard compass (1902); and the Silva orienteering compass (Sweden 1932). Liquid compasses returned in the 19th Century, with the first liquid mariner’s compass invented by Francis Crow (UK) in 1813. In 1860, Edward Samuel Ritchie invented an improved liquid marine compass that was adopted by the U.S. Navy. Finnish inventor Tuomas Vohlonen produced a much-improved liquid compass in 1936 that led to today’s models.

The first Chinese compasses used a spoon on a flat board. It is not clear if this image shows an actual Han Dynasty compass or a reproduction.

SADDLE – 200 BCE – China

There is evidence that Assyrian horse riders used cloths and pads on the horse’s back, held on with a girth or surcingle that included breast straps and cruppers, as far back as 700 BCE. These primitive saddles were often elaborately ornamented. Scythians and Sarmatians (in what is now Iran) had treeless padded saddles by the 7th Century BCE. By 500-400 BCE, riders in Siberia, Armenia and Assyria had developed more complex framed saddles with attributes such as facings, thongs, cruppers, breastplates and shabracks. Treed saddles were not invented until 200 BCE, in China. A treed saddle has a solid frame or structure underneath, called a tree, that protects the horse’s back from the full weight of the rider and raises the rider to a better position. The Romans developed a four-horn treed saddle in the 1st Century BCE. The first evidence of stirrups is from the 2nd Century BCE in India, but the modern stirrup was invented in China sometime before 302 CE. In the Middle Ages, Europeans developed saddles with a higher cantle and pommel and a stronger wooden tree. These saddles were was padded with wool or horsehair and covered in leather or textiles. In the 18th and 19th Centuries, the traditional split between the English and Western saddles arose, although there are many other varieties. More recently, some have advocated a return to treeless saddles.

A reconstruction of a Roman four-horn saddle from 100 BC-100 CE.

PAPER – 200-100 BCE (Han Dynasty) – China

Although the invention of paper is traditionally attributed to Ts’ai Lun in 105 CE, strong evidence indicates that the pulp process was developed in China some time earlier in the 2nd Century BCE, during the Han Dynasty. The first recipe may have included tree bark, cloth rags, hemp and fishing nets. The earliest use of paper was to wrap and pad delicate objects, such as mirrors. The use of paper for writing is first seen in the 3rd Century CE. Paper was used as toilet tissue from at least the 6th Century CE. In the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), paper was used to make tea bags, paper cups and paper napkins. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), paper was used to make bank notes, or currency. Paper was introduced into Japan between 280 and 610 CE. In America, the Mayans developed a type of paper called amatl, made from tree bark, beginning in the 5th Century CE. The Islamic world obtained the secret of papermaking by the 6th Century CE, when it was being made in Pakistan. The knowledge had spread to Baghdad by 793 CE, to Egypt by 900 CE and to Morocco by 1100 CE. In Baghdad, an inventor discovered a way to make thicker sheets of paper, a crucial development. In 8th Century Samarkand (modern-day Uzbekistan), the first water-powered pulp mills were built. In 1035, a traveler noted that Cairo market sellers were wrapping customers’ purchases in paper. The first European papermaking occurred in Toledo, Spain in 1085 CE. The first French paper mill was established by 1190 CE. Arab merchants introduced paper into India in the 13th Century. The first definitive reference to a water-powered paper mill in Europe is from 1282 in Spain. Paper was expensive to make until after 1844, when Charles Fenerty (Canada) and F.G. Keller (Germany) independently developed processes for using wood pulp to make paper, instead of recycled fibers.

This hemp paper, from 100 BCE in China, was used as wrapping paper.

ASTROLABE – 150 BCE – Hipparchus – Ancient Greece

The astrolabe is a complex instrument that can determine angles of slope (tilt), or elevation or depression of an object. It can help with navigation, surveying, determining time and the locations of heavenly bodies. Invention of the first astrolabe is attributed to Hellenistic Greek scientist Hipparchus in about 150 BCE, but there is some evidence that the instrument existed as early as 225 BCE. Severus Sebokht (Mesopotamia) refers to a brass astrolabe in the mid-5th Century CE. In the Middle Ages, Islamic scientists improved the astrolabe, adding angular scales and circles indicating azimuths on the horizon. Invention of the Islamic astrolabe is traditionally attributed to 8th Century CE Persian mathematician Muhammad al-Fazari. The oldest surviving astrolabe is Islamic and dated 927-928 CE. The earliest known European astrolabe is a brass instrument from 10th Century Spain. Islamic astronomers invented the spherical astrolabe as early as 892-902 CE. Sharaf al-Din al-Tusi (Persia) invented the linear astrolabe in the 12th Century and Abi Bakr (Persia) invented the geared mechanical astrolabe in 1235. European use became widespread by the 13th Century; the astrolabe peaked in popularity in the 15th and 16th Centuries. By the 16th Century, Europeans such as Johannes Stöffler and Georg Hartmann (Germany) were using batch production to make astrolabes. Astrolabe use declined in the last half of the 17th Century, due to the increased accuracy of the clock and the invention of the telescope.

This astrolabe was made in Arabia in 927 CE. Muslim astronomers significantly improved on earlier designs.

GLASS MIRROR – 1st Century CE – Lebanon; Ancient Rome

The first mirrors were made of obsidian, polished bronze or copper and date from 6000 BCE in Anatolia, 4000 BCE in Mesopotamia, 3000 BCE in Egypt and 2000 BCE in Mesoamerica. The first mirrors made of metal-coated glass are said to have come from Sidon (in modern-day Lebanon). Pliny described a glass mirror backed by gold leaf in 77 CE. The Chinese began making mirrors backed with a silver-mercury amalgam in 500 CE. In the 16th Century, Venetian manufacturers began making superior glass mirrors backed with a tin-mercury amalgam.

This is a lead cast for a glass mirror that was made in Ancient Rome in the 2nd or 3rd Century CE.

INDOOR PLUMBING – 100 CE – Ancient Rome

Although the Indus Valley culture, the Mayans in Mesoamerica and some Scottish villages show evidence of indoor plumbing before the Romans, the Roman system of aqueducts, public baths, wells and fountains, with lead pipes, was the most sophisticated plumbing and sanitation system developed to date. After the fall of the Roman Empire, little in the way of indoor plumbing existed for nearly a millenium. In the 16th Century, the English restored the Roman baths at Bath and uncovered their technology. There was little in the way of advancement until 1810, when the English Regency shower was invented. In 1829, the Tremont Hotel in Boston became the first hotel in modern times with indoor plumbing. In 1848, England passed a law requiring sanitary arrangements in every house, and provided money for a sewer system. Galvanized iron piping became popular in the late 19th Century. In the mid-20th Century, as awareness of lead poisoning grew, plumbers began to use copper piping as a substitute for older lead pipes.

Like many Roman homes, the Colosseum had an elaborate indoor plumbing system, part of which is shown here.

PORCELAIN – 196-220 CE (Eastern Han Dynasty) – China

Porcelain is a type of ceramic made by heating a form of clay called kaolin with other materials in a kiln at temperatures from 1,200-1,400 Centigrade (2,192-2,552 Farenheit). Because porcelain originated in China, it is sometimes referred to in English-speaking countries as ‘china.’ There is debate among scholars about the date of the first true porcelain. Most believe it was invented during the Eastern Han Dynasty (196-220 CE) and perfected during the Sui (581-618 CE) and Tang Dynasties (618-907). Others believe that true porcelain making only began in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) and the earlier ceramics were made of proto-porcelain. Most early attempts by Europeans to make porcelain failed, although Germans Von Tschirnhaus and Böttger were able to make porcelain at Meissen in 1708. Europeans were aided by a French Jesuit priest, Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles, who brought back many porcelain-making secrets from China and published them in 1712. Soft-paste porcelain was made in France before 1702 and in England in 1742. In 1749, Thomas Frye (UK) invented bone china, which contained bone ash. Josiah Spode (UK) perfected the recipe.

A white porcelain vase dating from the Tang Dynasty, 618-907 CE.

HINDU-ARABIC NUMERAL SYSTEM – 1-400 CE – India

Also known as the Indo-Arabic Counting System, the Hindu-Arabic Numeral System was the first counting system to include a zero and is the basis for most of subsequent mathematics. This positional decimal numeral system was invented in India, but there is much debate about the date. Some scholars believe there is evidence for a 1st Century CE date, while others say the earliest evidence is from the 3rd or 4th Century CE. All agree that the system was in use by 600 CE. The system began to spread elsewhere: Severus Sebokht mentions it in 662 CE in Syria and Muslim scholar al-Qifti cites an encounter between a Caliph and an Indian mathematics book in 776 CE. Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi gave a treatise on the system in an 825 CE book and Arab mathematician Al-Kindi did the same in 830 CE. Arabic numerals first appear in Europe in a 976 CE Spanish text. Italian mathematician Fibonacci sought to promote the system in a book published in 1202, but the system did not become standard in Europe until after the printing press was invented in the 1540s.

This chart shows the changes in numerals from Hindu India, to the Islamic world, and then to Europe.

HORSE COLLAR – 450-500 CE – China

Before the invention of the true horse collar, many ancient civilizations had developed the throat-girth harness, which had the drawback of cutting off the horse’s air supply when the horse pulled hard enough. The throat-girth harness was is found in Chaldea (3000-2000 BCE); Crete (2700-1450 BCE); Sumer and Assyria (1400-800 BCE); Egypt (1570-1070 BCE); China (1600-1050 BCE); Greece (550-323 BCE); and Rome (510 BCE – 476 CE). The next step was the breast-strap or breastcollar harness, which was developed in China during the Warring States period (481-221 BCE); it spread to Central Asia by the 7th Century CE and Europe by the 8th and 9th Centuries. The breastcollar harness caused fewer problems for the horse, but it was not efficient. Horses did not become effective workers until a fully developed collar harness was developed in China about 450-500 CE that allowed the horse to fully exert itself without restricting air flow. The horse collar spread to Europe as early as 800 CE and became universal by the 12th Century.

A depiction of a European horse collar and harness, from about 800 CE.

TOILET PAPER – 589 CE (Sui Dynasty) – China

Prior to the introduction of toilet paper, people around the world used various methods to clean themselves, including: wool, lace, hemp, rags, leaves, wood shavings, grass, hay, stone, sand, moss, water, snow, maize, ferns, may apple plant husks, fruit skins, seashells, corncobs, pebbles, broken pottery shards, a sponge on a stick or their hands. The use of toilet paper began in China at some time prior to 589 CE. Modern toilet paper was invented in 1857 by Joseph Gayetty (US). Toilet paper rolls and dispensers were patented by Seth Wheeler (US) in 1883.

This 20th Century toilet paper advertisement attempts to sum up the history of personal hygiene.

PAPER MONEY – 600-700 CE – China

Paper money was useful when money needed to be mobile or where metal was scarce, but it was also risky because it required users to have confidence that it was backed by something with real value and would be accepted in trade. China began using local issues of paper money in the 7th Century (Tang Dynasty), but did not make paper money a regular practice until the late 13th Century, in the Song Dynasty, when a nationwide standard currency was issued. The Chinese continued to use paper money until the 1400s, then abruptly abandoned the practice for 300 years. Europeans were aware of paper money in the 13th Century through travelers such as Marco Polo, but although promissory notes were common in Italy and Flanders in the Middle Ages, Europe did not adopt the practice until the end of the 17th Century. In 1661, Sweden became the first European country to issue paper money. The Massachusetts Bay Colony began circulating paper money in the early 1690s. John Law (Scotland) introduced paper money in France in 1716 to deal with a metals shortage.

This bank note was issued in China in 1380.

TOOTHBRUSH – 619-907 CE – China

Before the toothbrush, there was the chew stick, a twig from a tree with antimicrobial properties, such as the toothbrush tree (Salvadora persica) in Africa. There is early evidence of chew sticks in Mesopotamia (3500 BCE), Egypt (3000 BCE) and China (1600 BCE). The predecessor to the modern toothbrush was invented during the Tang Dynasty (619-907 CE) in China, when hog bristles were attached to a handle made of bamboo or bone. Travellers brought back Chinese toothbrushes to Europe in the 17th Century, but Europeans found the hog bristles too rough and substituted softer horsehair, William Addis (UK) produced the first mass-marketed toothbrush in 1780. H.N. Wadsworth (US) patented a Siberian boar’s hair toothbrush in 1857, but didn’t produce it until 1885. In the 20th Century, celluloid replaced bone in the handle. DuPont introduced the first nylon bristle brush in 1938. The first electric toothbrush was invented in Sweden in 1954. Johnson & Johnson invented the ‘Reach’ toothbrush in the 1980s.

This horsehair toothbrush, dating to 1795, is said to have been used by Napoleon.

WINDMILL – 800-900 CE – Persia

Precursors to the windmill include the windwheel of Heron of Alexandria, a Greek engineer, and the prayer wheels that have been used in Tibet and China since the 4th Century. A windmill uses the power of the wind to create energy; the first windmills were used to mill grain. The first practical windmills were made in Persia in the 9th Century and had ‘sails’ that rotated in a horizontal plane, not vertical as we normally see in the West. This technology spread throughout the Middle East and Central Asia and later to China and India. A visitor to China in 1219 remarked on a horizontal windmill he saw there. Vertical windmills first appear in an area of Northern Europe (France, England and Flanders) from about 1175. The earliest type of European windmill was probably a post mill. By the late 13th Century, masonry tower mills were introduced – a later 17th Century variation is the smock mill. In the 14th Century, hollow-post mills arise for particular purposes.

These windmills in Iran were originally built between 500 and 900 CE.

GUNPOWDER – 800-900 CE – China

Historians believe that Chinese alchemists invented gunpowder in the 9th Century CE while they were looking for a chemical that would make them immortal. They soon found out the explosive potential for their discovery and it was used in creating many weapons, including fireworks (10th Century CE), flamethrowers (1000) and bombs (1220). The Chinese had perfected the recipe by the mid-14th Century. The Mongols learned about gunpowder when they conquered China in the mid-13th Century and spread it throughout the world during their subsequent invasions. The Arabic empire obtained gunpowder in the mid-13th Century. The Mamluks used cannons against the Mongols in 1260. In 1270, Syrian chemist Hasan al-Rammah described a method for purifying saltpeter in making gunpowder. Europeans first saw gunpowder used by the Mongols at the Battle of Mohi in 1241. Roger Bacon (UK) referred to gunpowder in a 1267 book. The first known use of gunpowder used by Europeans in battle was during the 1262 siege of the Spanish city of Niebla by Castilian King Alfonso X. By 1350, cannons were a common sight in European wars. India had gunpowder technology from at least 1366 CE, if not earlier. In the late 14th Century, European powdermakers began adding liquid and ‘corning’ the powder, which improved performance significantly.

This gunpowder-charged hand cannon, an early handgun, was used by the Chinese during the Yuan Dynasty, in the 14th Century.

PLAYING CARDS – 868 CE (Tang Dynasty) – China

The first reference to a card game comes from 868 CE, when writer Su E, described the Emperor’s daughter playing the ‘leaf game’ with her in-laws. Playing cards were found throughout Asia by the 11th Century. Europeans discovered card playing in the early 14th Century, probably from China by way of Egypt. A reference to card playing is found in a Spanish book dating to 1334. The earliest cards were handmade and expensive. Cheaper printed woodcut decks appeared in the 15th Century. The four suits common to most of the world – spades, hearts, diamonds and clubs – came about in France about 1480.

A Chinese playing card from the Ming Dynasty, about 1400 CE.

GUN – 900-1000 CE – China

Most historians believe that the first gun was the Chinese fire lance, a gunpowder-filled tube at the end of a spear that shot out flames and sometimes shrapnel, which was invented in the 10th Century. Eventually, the paper and bamboo of the fire lance were replaced by metal, and the shrapnel was replaced by a projectile that fit the size of the barrel to create the first hand cannon. Such a metallic gun is depicted in a 12th Century Chinese cave sculpture. An existing example is made of bronze and dates to 1288. After the Mongol invasion of China in the 13th Century, guns spread around the world. The Arabs saw the Mongols use cannons in 1260 and they obtained the technology by the 14th Century. There is a record of guns being used in Vietnam in 1390. The first references to guns in Europe date from the 1340s, in the UK. A Russian chronicle dating to 1382 mentions the use of firearms by people defending Moscow from the Golden Horde. The oldest existing firearm from Europe was found in Estonia and dates to 1396. In the late 14th Century, portable hand-held cannons were developed in Europe. By the late 15th Century, the infantry of the Ottoman Empire was equipped with personal firearms. The arquebus – a muzzle-loaded smoothbore firearm with a matchlock – was invented in the 15th Century, improved in the 16th Century and largely replaced by the end of the 17th Century. The Japanese obtained firearms from the Portuguese in the 16th Century. Also in the 16th Century, a heavier version of the arquebus called the musket was first introduced. The term musket covers a variety of long muzzle-loaded guns, but the earliest versions were very heavy and had a matchlock. As the musket became lighter and other improvements were made (such as a change to the flintlock firing mechanism in the 17th Century), it began to outcompete the arquebus, which was outmoded by the 18th Century. The change from smoothbore barrels to rifled barrels in the 18th Century (although instances of rifling go back to the 15th Century) meant a huge leap in accuracy. A major advance was made by Claude-Étienne Minié (France), who developed the Minié ball in 1847 and the Minié rifle in 1849; these decreased loading time, increased range from 50 yards to 300 yards, and increased accuracy. The first breech loading rifle was the Germany Dreyse Needle gun of 1836, followed by the French Tabatière in 1857. The French were the first to add a bolt-action mechanism in 1866 with the Chassepot.

This Chinese Buddhist illustration depicts a demon using a fire lance (upper right). The image dates to either is either the 10th or 12th Century CE

MECHANICAL CLOCK – 976 – Zhang Sixun – China

Prior to the invention of the mechanical clock, humans kept time using sundials (a type of shadow clock), hourglasses, water clocks and candle clocks. Beginning in the 7th Century, Chinese inventors improved on the water clock by adding escapements. Islamic scientists had also made improvements on the water clock, including a gift by Harun al-Rashid of Baghdad to Charlemagne in 797 CE. In 976, Zhang Sixun (China) was the first to replace the water in his clock tower with mercury. In 1000 CE, Pope Sylvester brought water clocks to Europe. In 1088, Su Song (China) further improved on Zhang’s design in his astronomical clock tower, nicknamed, ‘Cosmic Engine.’ The first geared water clock was invented by Arab engineer Ibn Khalaf al-Muradi in Spain in the 11th Century. There is some evidence of mechanical clocks, which used falling weights instead of water, in Europe in 1176 (France) and 1198 (England). Al-Jazari (Mesopotamia) built numerous clocks in the early 13th Century and there is evidence of an Arabic mechanical clock in a 1277 Spanish book. There is also evidence of mechanical clocks in England in 1283 and 1292, as well as Italy and France. The oldest surviving mechanical clock is at Salisbury Cathedral (UK) and dates to 1386. Spring-driven clocks first appeared in the 15th Century. Clocks indicating minutes and seconds also begin to appear in the 15th Century. Jost Bürgi (Switzerland) invented the cross-beat escapement in 1584. Around the same time, the first alarm clocks were invented.

An illustration from a book by Su Song showing his 1088 clock tower.

MOVABLE TYPE PRINTING – 1040 – Bi Sheng – China

Movable type printing replaced woodblock printing. Bi Sheng (China) invented movable type printing in 1040. He first made the characters from wood but found that ceramics worked better. Choe Yun-ui of Korea was the first to use metal for the type, in 1234. The technology was not well-adapted to the Chinese language, with its thousands of characters. For some reason, the invention did not spread to Europe and it was not until 1450 that Johannes Gutenberg of Germany independently rediscovered movable type.

Pages from the Korean book Jikji, printed in 1377 using metal movable type printing.

BUTTONS – 1200-1300 – Germany

Buttons had been used as ornaments in various parts of the world as far back as 2800-2600 BCE. The oldest functional buttons – that is, buttons used to fasten clothing – were found in the 9th Century CE graves of Hungarian warriors. Buttons designed for clothes with buttonholes do not appear until the 13th Century, in Germany. Clothing styles had changed at about that time, with more form-fitting apparel requiring numerous fasteners. The increase in button manufacturing is evidenced by the creation of a Paris button-makers’ guild in 1250.

A button from the UK, dating from the 15th Century.

EYEGLASSES – 1286 – Alessandro di Spina – Italy

There are references going back as far as the 5th Century BCE to the use of lenses, jewels or water-filled globes to correct vision, but it was only after an Arabic book on optics was translated into Latin in the 12th Century that the stage was set for the invention of true eyeglasses. According to a Medieval historian, an anonymous Italian invented eyeglasses in 1286 but was “unwilling to share them.” Soon afterwards, another Italian, Alessandro di Spina, also invented eyeglasses and “shared them with everyone.” The first eyeglasses used convex lenses to correct both farsightedness (hyperopia) and presbyobia. They were designed to be held in the hand or pinched onto the nose (pince-nez). Some have speculated that eyeglasses originated in India prior to the 13th Century. The earliest depiction of eyeglasses is Tommaso da Modena’s 1352 portrait of Cardinal Hugh de Provence. A German altarpiece from 1403 also shows the invention. The first glasses that extended over the ears were made in the early 18th Century.

This portrait of Hugo of Provence, painted by Tommaso da Modena in 1352, is the first known depiction of eyeglasses.

CONDOMS – 15th Century – Europe, China

There is some evidence of glans-only condoms made of oiled silk paper, lamb intestines, tortiseshell or animal horn in China and Japan in the 14th Century. There is an unambiguous reference to a glans-only condom made of chemically-treated linen in a 1564 treatise by Gabriele Falloppio (Italy) about the recent syphilis outbreak, in which it is discussed as a means of preventing transmission of the disease. In 1605, a Catholic theologian condemned birth control through condoms as immoral. At some point in the 1600s, full-length condoms appeared, usually made from animal bladders or intestines. The first rubber condom was produced in 1855, and the first latex condom was produced by Youngs Rubber Company (US) in 1929.

This condom, made from pig’s intestines, dates to 1640.

PRINTING PRESS – 1450 – Johannes Gutenberg – Germany

While movable type was first invented in 11th Century China, it was reinvented independently by Johannesburg Gutenberg in Germany 300 years later. Gutenberg’s major innovation was to adapt the already-existing screw press into a machine that could print on paper. He also created a special metal alloy for the type; invented a device for moving type quickly; and developed a new, superior ink. The result was high quality printing at a very fast pace. The invention quickly spread across the European continent, putting books into the hands of Everyman. The cast iron printing press – which reduced the force needed and doubled the size of the printed area – was invented by Lord Stanhope (UK) in 1800. Between 1802 and 1818, Friedrich Koenig (Germany) created a steam-powered press with rotary cylinders instead of a flatbed. In 1843, Richard M. Hoe (US) invented a steam-powered rotary printing press.

This replica of Gutenberg’s printing press (left) and workshop is located in St. George’s, Bermuda.

SCREWDRIVER – 1450-1470 – France or Germany

The earliest screwdrivers had pear-shaped handles and were made for slotted screws. The first evidence of screwdrivers is from France and Germany in 1450-1470. At that time, screws were used to construct screw-cutting lathes, secure breastplates, backplates, and helmets on medieval jousting armor, and eventually for multiple parts of firearms, particularly the matchlock. Diversification of the many types of screwdrivers did not emerge until much later. In 1908, P.L. Robertson (Canada) was the first to successfully commercialize square socket-head screws and a square screwdriver to screw them in. Henry Philips (US) invented the Philips or cross-head screw in 1934. At the same time, the cross-head screwdriver was invented. More modern variations are the ratchet screwdriver, which was introduced about 1850, and the power screwdriver, introduced by Black & Decker in 1923.

This 1480 illustration from the Housebook of Wolfegg Castle in Germany contains the earliest depiction of a screwdriver (center left, top third).

PARACHUTE – 1470-1485 – Leonardo da Vinci – Italy

Leonardo da Vinci (Italy) designed the first parachute between 1470 and 1485, but there is no evidence that he or anyone else actually built one to see if it would work. Leonardo’s plan required a fixed triangular frame made of wood and covered with linen. It wasn’t until 2000 that the design was put to the test – Adrian Nicholas (UK) built a prototype using only materials available in 15th Century Milan and jumped out of a hot-air balloon at 10,000 feet. It worked (see photo).

Da Vinci’s 15th Century parachute design.

Adrian Nicholas floats to earth on a Da Vinci parachute in 2000.

DOUBLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING – 1494 – Luca Pacioli – Italy

Evidence of double-entry bookkeeping is found in the papers of some Florentine merchants as early as the end of the 13th Century. The new system became more common among Italian and German merchants and bankers through the 14th Century. But it was Luca Pacioli (Italy), a Franciscan friar and mathematician, who in a 1494 book was the first to codify the new accounting system, and established the golden rules of accounting and the equation: Equity = Assets – Liabilities.

A 1496 portrait of Fra Luca Pacioli, attributed to Jacopo de Barbari.

PENCIL – 1560 – Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti – Italy

The first pencils were sticks of graphite derived from a huge graphite deposit found in Cumbria, England in the early 1500s. In 1560, Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti (Italy) were the first to encase the graphic stick in wood. In 1795, Frenchman Nicholas Jacques Conté (France) mixed powdered graphite with clay to form rods that he fired in a kiln. By changing the ratio of elements, he could change the hardness of the graphite rod.

This 17th Century graphite pencil was found in the roof of a house in Germany.

MODERN CALENDAR – 1582 – Pope Gregory XIII – Italy

The modern calendar had its origins in the Roman calendar introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE and then revised in 45 BCE as the Julian calendar. In the Julian calendar, each year consisted of 365 days divided into 12 months, with a leap year every four years, creating an average year of 365.25 days. Because a true solar year is slightly less than 365.25 days, over the centuries, the Julian calendar became out of sync with the seasons and religious holidays. This led Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to revise the calendar to skip three leap years every four centuries, which keeps the calendar in line with the seasons to this day. The average year is now 365.2425 days. Although some non-Western countries and religious groups maintain their own calendars, the Gregorian calendar is used universally for trade and international relations, including by the United Nations.

Camillo Rusconi’s carvings on the tomb of Pope Gregory XIII in St. Peter’s Basilica show the introduction of the Gregorian calendar.

COMPOUND OPTICAL MICROSCOPE – 1590-1600 – Hans Lippershey & Zacharias Jansen – The Netherlands

Roger Bacon first proposed the idea of a microscope in 1267, but it wasn’t until the late 1500s that two Dutch eyeglass makers, Hans Lippershey & Zacharias Jansen, made the first compound optical microscope. (‘Optical’ because it used visible light and lenses to magnify objects and ‘compound’ because it used multiple lenses, allowing for much greater magnification than the single lens, or simple optical microscope.) Galileo Galilei developed a compound microscope in 1609 in Italy, while Dutchman Cornelius Drebbel created one in 1619. The biggest boost for the microscope came from Robert Hooke, of the UK, who published a book of drawings from the microscope entitled Micrographia in 1665, containing numerous scientific discoveries, including the first description of a biological cell.

This microscope was built by Christopher Cook for Robert Hooke in the 17th Century.

MODERN FLUSH TOILET – 1596 – Sir John Harrington – UK

Sir John Harrington built a flush toilet and installed it in his house in about 1594, then announced the new invention in a 1596 book. He later installed one for his godmother, Queen Elizabeth, who didn’t like to sit on the ‘throne’ because the flushing mechanism was ‘too noisy.’ The invention didn’t catch on at the time, and was essentially reinvented separately by J.F. Brondel, Alexander Cummings, Samuel Prosser and Joseph Bramah, all of the UK, in the 18th Century.

An antique toilet.

OPTICAL TELESCOPE – 1608 – Hans Lippershey & Zacharias Jansen – The Netherlands

The first telescopes were refractors because they used lenses to collect and magnify light. The earliest versions were made by Hans Lippershey, Zacharias Jansen and Jacob Metius, all from The Netherlands. Galileo Galilei (Italy) built a refractor telescope in 1609. In 1655 Christiaan Huygens (The Netherlands) developed a compound eyepiece refractor based on a theory by Johannes Kepler. In 1668, Isaac Newton (UK) invented the first reflector telescope, which used a mirror instead of a lens to collect light. Laurent Cassegrain of France improved on the reflector in 1672. Further improvements were made throughout the 18th Century.

Two of Galileo’s original telescopes from the early 1600s.

THERMOMETER – 1611-1613 – Francesco Sagredo or Santorio Santorio – Italy

Ancient Greek scientists had invented primitive thermoscopes, based on the principles that certain substances expanded when heated. Scientists in Europe, including Galileo Galilei, developed more sophisticated thermoscopes in the 16th and 17th Centuries. In 1611-1613, in Italy, when either Francesco Sagredo or Santorio Santorio first added a scale to a thermoscope, the first thermometer was born. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (Netherlands/Germany/Poland) invented the alcohol thermometer in 1709 and the mercury thermometer in 1718. Each inventor used a different scale for his thermometer until Farenheit suggested the scale that bears his name in 1724. That scale was becoming the standard when, in 1742, Anders Celsius (Sweden) suggested a different scale. The two scales have been in competition ever since.

One of the original thermometers made by Daniel Farenheit, dating to between 1714 and 1724.

SUBMARINE – 1620 – Cornelius Drebbel – The Netherlands

The first submarine, the Drebbel, was designed by William Bourne and built by Cornelius Drebbel for James I of England in 1620; it was propelled by oars. The first military submarine, the Turtle, was built by David Bushnell (US) to aid the American Revolution in 1775. It used screws for propulsion. Subsequent human-powered subs were made and tested in France, Ecuador, Bavaria, Chile and both sides in the U.S. Civil War, leading to numerous drownings. The U.S. Navy’s first submarine, the French-designed Alligator, was the first to use compressed air and an air filtration system. The French Plongeur, launched in 1863, was the first submarine that did not rely on human power. A Spanish model from 1867, the Ictineo II, designed by Narcis Monturiol (Spain), was powered by a combustion engine that was air independent. Polish inventor Stefan Drzewiecki built the first electric-powered submarine in 1884. In 1896, Irish inventor John Philip Holland built the first submarine that used internal combustion engines on the surface and electric battery power underwater.

A replica of Monturiol’s 1867 Ictineo II in Barcelona, Spain.

PENDULUM CLOCK – 1656 – Christiaan Huygens – The Netherlands

The pendulum clock uses a weight that swings back and forth in a precise time interval, thus making this type of clock much more precise than previous designs. Galileo Galilei (Italy) had been exploring the properties of pendulums since 1602, and he came up with the idea for a pendulum clock in 1637, but died without completing it. Huygens (The Netherlands), with the assistance of clockmaker Salomon Coster, designed and built a pendulum clock that realized Galileo’s dream.

A drawing of Huygens’s first pendulum clock, from 1656.

STEAM ENGINE – 1698 – Thomas Savery – UK

Although numerous attempts were made to harness the power of steam, Briton Thomas Savery’s pistonless steam pump was the first practical design. It was Thomas Newcomen’s (UK) 1712 piston-driven “atmospheric-engine”, though, that proved to be the first commercially viable steam engine. By 1774, James Watt (UK) had made several major improvements to the Newcomen engine that hugely increased its efficiency. Further improvements followed throughout the 19th Century.

A drawing of the Savery steam engine, built in 1698.

SEXTANT – 1757 – John Campbell and John Bird – UK

In about 1730, John Hadley (UK) and Thomas Godfrey (US) independently invented the octant, a navigational instrument that measures the angle between two objects, usually a heavenly body and the horizon. (Isaac Newton had invented a similar device, a reflecting quadrant, in 1699, but the invention was not published until 1742.) Admiral John Campbell (UK) of the Royal Navy suggested several improvements to Hadley’s octant. Based on these suggestions, John Bird (UK) designed and built the first sextant in 1757.

An early sextant made by John Bird, probably in the 1760s.

REFRIGERATOR – 1748 – William Cullen – Scotland

William Cullen (Scotland) invented artificial refrigeration at the University of Glasgow in 1748. Oliver Evans (US) created the vapor-compression refrigeration process in 1805. Jacob Perkins (US) took Evans’s process and built the first actual refrigerator in 1834. John Gorrie (US) invented the first mechanical refrigeration unit in 1841. Further improvements were made by Alexander Twining (US) in 1853; James Harrison (Scotland/Australia) in 1856; Ferdinand Carré (France) in 1859; Andrew Muhl (France/US) in 1867 and Carl von Linde (Germany) in 1895.

This photo is said to show a Jacob Perkins refrigerator built in the early 19th Century.

SUNGLASSES – 1752 – James Ayscough – UK

James Ayscough (UK) is usually cited as the inventor of sunglasses because he experimented with tinted lenses (usually blue or green) in eyeglasses beginning in 1752. However, Ayscough was not concerned about the sun, but with correcting impaired vision. At some point later, yellow/amber and brown tinted lenses were prescribed for those suffering from syphilis, which increased sensitivity to light. Sunglasses became popular with the public only in the 20th Century, particularly after Sam Foster (US) began selling his Foster Grant sunglasses on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1929. Polarized sunglasses were invented by Edwin Land (US) of Polaroid in 1936.

The wearing of sunglasses by celebrities like Ginger Rogers, shown here in 1936, increased their popularity.

ROLLER SKATES – 1760 – Joseph Merlin – Belgium

Joseph Merlin’s skates of 1760 replaced the blades of ice skates with wheels, creating the first inline skates. They were hard to steer and hard to stop and weren’t very popular. Mr. Petitbled, from France invented a three-wheeled inline skate in 1819. Robert Tyers (UK) tried five wheels in 1823. August Lohner, of Austria made a skate with a tricycle design in 1828. Various inline skates were invented in the next 30 years until 1863, when James Plimpton (US) invented four-wheeled quad skates. These were safer and more maneuverable than earlier designs and quickly caught on. Inline skating returned to popularity in the 1980s and 1990s due to successful promotion by Rollerblade, Inc.

An 1879 newspaper ad for Plimpton skates.

STEAM-POWERED AUTOMOBILE – 1769 – Nicolas Joseph Cugnot – France

French inventor and military engineer Nicolas Cugnot created the first self-propelled mechanical vehicle – a steam-powered three-wheeled automobile – in 1769 for the French army. He built a larger version in 1771 – it could seat four passengers and sped along at 2.25 mph. Problems with weight distribution and boiler performance, however, led the French Army to abandon the project.

Cugnot’s 1771 ‘fadier a vapeur’ is now in a Paris museum.

ERASER – 1770 – Edward Naine – UK

The earliest erasers were made of wax, sandstone, pumice or stale bread. In 1770, both Joseph Priestley and Edward Naime (UK) independently discovered the power of raw rubber for removing pencil marks. (In fact the name ‘rubber’ comes from this quality.) Naime quickly marketed the item and is credited with the invention. Raw rubber was perishable, but after Charles Goodyear (US) invented vulcanization in 1839, he created durable rubber erasers. The final step came in 1858, when Hymen Lipman (US) attached an eraser to the end of a pencil, creating the first combination pencil/eraser.

Hymen Lipman’s patent for the pencil/eraser, which was eventually revoked because neither the pencil nor the eraser was new.

HOT-AIR BALLOON – 1783 – Joseph-Michel & Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier – France

The ability to raise small unmanned balloons into the air using hot air was known In China from the 3rd Century CE. The Montgolfier brothers built the first hot-air balloons capable of carrying human passengers in France in the late 18th Century. They tested their design first with no passengers on June 4, 1783, then on September 19, 1783 with a sheep, a duck and a rooster, who survived an eight-minute flight. Then, on November 21, 1783, French scientist Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d’Arlandes, an Army officer, climbed aboard a Montgolfier balloon to make the first untethered manned flight. They traveled for 25 minutes, covered a distance of five miles and attained an altitude of 3,000 feet before safely landing. Among those in the audience were King Louis XVI and Benjamin Franklin.

A 1786 illustration of the first manned balloon flight, just three years earlier.

MODERN PARACHUTE – 1783 – Louis-Sébastien Lenormand – France

Louis-Sébastien Lenormand (France) made the first modern parachute, which consisted of linen stretched over a wooden frame. He demonstrated the invention in 1783 by jumping off the tower of the Montpellier observatory. In 1785, Jean-Pierre Blanchard (France) showed that a parachute could be used to disembark from a hot-air balloon. Blanchard made the first folded silk parachute in the late 1790s. André Garnerin (France) was the first to make a jump using the silk design. Garnerin also invented the vented parachute, which had a more stable descent.

A drawing of Garnerin’s 1797 parachute, showing the view from above (left), ascending using a hot-air balloon (center) and descending with the parachute (right).

BIFOCAL LENS – 1784 – Benjamin Franklin – US