I created the meta-list below by collecting over 22 lists with titles like The Best Photography of All Time, The Greatest Photographs Ever, The Most Important Photos, The Most Iconic Photos, The Most Influential Photos. I also included the photographs highlighted in several history of photography books. In order to diversify the list, I also collected lists of the best photographs in particular genres, such as photojournalism, street photography, fashion photography, portraiture, nature and landscape photography and art photography. I then compiled all the lists into one meta-list to determine which photos were on the most lists. The most-listed photo was on 22 of the lists I found. The list below includes every photograph that was on at least three of the original lists, organized by rank (that is, with the photos on the most lists at the top). Photos that were on the same number of lists are organized chronologically. Each entry includes the number of lists the photo is on, the title (note that many photographs have multiple titles – I have tried to mention alternate titles in the text), the date (usually the date of the exposure, but sometimes the date of the print) and the photographer’s name. A short essay with additional salient information, such as the photographic equipment used, follows in most cases.

Note: These are not my personal opinions. The most-listed photos are not necessarily the best photos, they are the photos on the most “best photos” lists.

A few warnings: (1) some of the photos contained in these lists depict death and other tragic situations and may be disturbing; (2) nudity is a fairly common theme in art and fashion photography. I find some of the photographers’ depictions of women to be objectifying and misogynistic, but you be the judge. (3) Many of these photos are still under copyright, so please have respect for the photographers’ legal rights – I have added links to purchase prints in some cases. I believe my use of these lower resolution images falls under the doctrine of fair use and also serves an educational purpose. Don’t forget to click on the photos to enlarge them.

For a longer list with more photographs, go to Best Photography of All Time: Chronological I and Chronological II, a two-part chronological survey of photos on two or more of the lists described above. For a chronological list of the best photographers and their best photos, including portraits of the photographers, go here.

On 22 Lists

Migrant Mother – Nipomo, California (1936) – Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange was working as a photographer for the U.S. Resettlement Administration in early 1936 when she visited California to photograph migrant farm laborers. Lange met Florence Owens Thompson and her children in a migrant camp in Nipomo, California and took a series of photographs, including this iconic image of the Great Depression. Thompson told Lange she was 32 years old and that she, her husband and seven children had been living on what vegetables they could find in the surrounding fields and some birds that the children had killed. Lange used a 4 X 5 Graflex camera for this enduring shot.

On 14 Lists

View from the Window at Le Gras (1826) – Nicéphore Niépce

This view from the window of French inventor Nicéphore Niépce is believed to be the first permanent photograph ever made. The process Niépce called heliography involved setting up a camera obscura in the window of his home in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes and focusing it onto a pewter plate measuring 6.4 inches by 8 inches that he covered with bitumen. After an exposure of at least eight hours (an inference based on the sunlight illuminating both sides of the street), but possibly as long as several days (based on attempts to recreate the event), the bitumen hardened in the brightly lit areas, while the bitumen in the dark areas was washed away with oil of lavender mixed with white petroleum. Unlike prior attempts to capture the images created by the camera obscura, the resulting photograph was permanent, although the image was only visible when the pewter plate was held at an angle. The plate disappeared about 1905 but was rediscovered by historian Helmut Gernsheim in 1952. Gernsheim had a modern photographic copy made (damaging the original in the process) and then heavily retouched it to create the image shown above. The original heliograph plate (shown below) is now at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

On 13 lists

Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death (1936) – Robert Capa

Hungarian photographer Robert Capa was only 22 years old in September 1936 when he received an assignment to photograph the Loyalist militia in the Spanish Civil War. When the above photo (also known as Death of a Loyalist Soldier), was published in the French magazine VU and later in Life, it was identified as taking place during a battle at Cerro Murino. The soldier was later identified as Federico Borrell Garcia, who was killed at Cerro Murino. But in the 1970s, expert analysis of the background landscape proved that the location of the photo is not Cerro Murino but Espejo, 30 miles away and far from any fighting. Many now believe that Capa staged the famous photograph with models, not real soldiers. Others agree that the location of the photo is Espejo and the man is not Federico Borrell Garcia, but the photo may still show a soldier “at the moment of death.”

General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner in Saigon (1968)

– Eddie Adams

Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams, an American, won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography and a World Press Photo award for this photo of South Vietnamese police chief General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executing Viet Cong prisoner Nguyễn Văn Lém on a street in the Cholon section of Saigon, on February 1, 1968, at the beginning of the Tet Offensive. Adams was photographing the prisoner and his captors when General Loan approached and pointed a gun at the prisoner’s head, as was common during interrogations. Instead of using the gun as a threat, Loan suddenly shot and killed Lem there on the street. NBC-TV captured the event on video. The photo by Adams spread around the globe almost instantly. Although the Vietcong prisoner was accused of killing civilians as part of a ‘revenge squad’, the photograph destroyed the reputation of General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan, so much so that Adams wrote in Time magazine, “The general killed the Vietcong, but I killed the general with my camera.”

On 12 lists

The Steerage (1907) – Alfred Stieglitz

When American photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his family traveled to Europe in a first class berth on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1907, the movement known as pictorialism had dominated photography for several decades. Pictorialists believed that photographs could become art, but only through the skillful manipulations of the artist at all stages of the photographic process. Straight photography, is it was known, was merely scientific representation of reality, with no artistic mediator. Pictorialist photos were rarely in sharp focus, and tended to have the quality of perfectly-composed paintings. Some pictorialists went even further and constructed artistic photographs by using multiple negatives. A gallery owner and magazine editor, Stieglitz was a major force behind the notion that photography could be art and was considered a pictorialist in 1907. Yet his photo of the steerage section of the Kaiser Wilhelm, with its sharp details and attention to structural lines, is anything but pictorialist. Instead, The Steerage eventually became evidence that straight photography could also be artistic. Stieglitz himself did not immediately recognize the importance of his watershed image – it was only four years later, in 1911, that he published it in one of his photography magazines. He published it again in 1913 and by 1915 devoted a whole issue of 291 magazine to The Steerage. By that time, the tide had begun to turn away from pictorialism and toward straight photography.

On 11 lists

Boulevard du Temple, Paris (1838) – Louis Daguerre

One of the earliest images produced by French photography pioneer Louis Daguerre is this 1838 daguerreotype of the Boulevard du Temple, a busy Paris street. It is not only one of the first photographs but is also probably the first time the new medium captured the image of a human being. The process Daguerre invented after the death of his mentor, Nicéphore Niépce, involved coating a thin silver-plated copper sheet with light-sensitive silver iodide and then exposing the plate in the camera. At first, exposure times were ten minutes or more, but over time, Daguerre was able to reduce the time to a few seconds. Daugerreotypes were known for their extremely detailed and realistic images in contrast to the grainy and fuzzy pictures resulting from other early photographic processes. Drawbacks of the process were that multiple prints could not be made from an exposure, and the images degraded by contact with air or by any scratching or friction. The Boulevard du Temple daugerreotype required a 10-minute exposure, which means that most pedestrians and carriages did not stand still long enough to be recorded, creating the illusion of a ghostly barren thoroughfare. The exception, in the lower left, is the man getting his shoes shined – he stood still long enough to register on film and in history as the first photographed human.

A Harvest of Death, Battlefield of Gettysburg (1863) – Timothy H. O’Sullivan

The Battle of Gettysburg, a turning point in the American Civil War, raged from July 1-3, 1863. Just two days later, photographers Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan arrived at battlefields that were still covered with the dead. Irish-born O’Sullivan had left Matthew Brady’s studio to work for Scottish-born Gardner, another Brady alumnus. His photo A Harvest of Death, taken July 5 or 6, became one of over 50 of his images reproduced in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866). We see Union and Confederate dead lying as they fell, with missing shoes and rifled pockets a sign that survivors had already come and taken anything they could make use of. The bloating of the corpses in the July sun has caused buttons to pop and clothing to open. Gardner’s original caption stated, in part, “It was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death’ … Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.” O’Sullivan used the collodion wet plate process, which by then had mostly replaced daugerreotypes, and Gardner made an albumen silver print for use in the Sketch Book.

V-J Day in Times Square “The Kiss” (1945) – Alfred Eisenstaedt

Born to a Jewish family in Germany, Alfred Eisenstaedt began his photography career as a Berlin freelancer in 1928, going full-time a year later. Before he emigrated to the US in 1935, Eisenstaedt had photographed, among others, Hitler, Goebbels and Mussolini. From his new home in New York City, he worked for Life magazine from 1936 to 1972, and saw 90 of his photographs featured on the cover of that highly-regarded publication. Eisenstaedt’s most famous Life photo was V-J Day in Times Square, also known as The Kiss, which shows an American sailor kissing a woman in a nurse’s white dress on August 14, 1945, the day Japan surrendered and World War II ended. Eisenstaedt used a Leica IIIa camera to capture the dark-and-light contrasting couple (if the sailor had worn white, Eisenstaedt said later, he wouldn’t have snapped the shutter). He was unable to obtain the names of the kisser and kissee; over the years, several people claimed to be the subjects. While most viewing the photo find that it expresses the joy and exuberance of the moment the war years ended, others have expressed concern that the sailor may be committing a socially-sanctioned sexual assault on the nurse, a view that may find unintentional support in the original Life photo caption: “In the middle of New York’s Times Square a white-clad girl clutches her purse and skirt as an uninhibited sailor plants his lips squarely on hers.”

On 10 lists

The Horse in Motion (series) (1878) – Eadweard Muybridge

In 1872, prominent California politician and businessman Leland Stanford asked English-born photographer Eadweard Muybridge to settle a question that had perplexed both experts and the public for years: Did all four of a running horse’s legs ever leave the ground? The horse’s legs moved too quickly for human eyes to see, but Stanford believed Muybridge could answer the question with photography. Muybridge initially experimented with a single camera using very short shutter speeds to photograph the horse Occident in 1872, 1873, and 1877. This resulted in one grainy photograph that showed all four feet off the ground, but retouching of the negative led experts to regard the resulting published print as a manipulated fake. In 1878, Muybridge tried a different approach. He set up 12 closely-spaced cameras along a racetrack with wires that the horse’s legs would trip, causing each camera to make an exposure of approximately 1/1000 of a second. With the press watching on June 15, 1878, a jockey ran the trotter Abe Edgington around the track at a 2:24 gait. Muybridge quickly developed the film – which showed all four legs off the ground in the ninth frame of the series – and presented it to the gathered crowd. During the next few days, Muybridge had several different horses run the track at different paces – trotting, cantering and galloping. Later in the same year, he published The Horse in Motion, a set of six photographic cards that included the 12 photos from the original Abe Edgington run (see image below) as well along with two other trots by the same horse on June 18 (one with eight frames and one with six frames), a trot by Occident, a canter by Mahomet on June 17 (six frames) and a gallop at a gait of 1:40 by thoroughbred Sallie Gardner on June 19 (12 frames). “Sallie Gardner” (see image above) became the most well-known of the six-pack of cards, perhaps because the second frame of the series illustrates the “flying horse” pose much better than the photographs of the trotters. Soon after the success of Horses in Motion, Muybridge doubled the number of cameras, resulting in even more detailed information about motion. Engravings of Muybridge’s series made it into newspapers and the front page of Scientific American magazine. Muybridge also converted the photos into silhouettes and then ran them in a zoopraxiscope to create an animated ‘movie’ of the horse galloping, one of the earliest precursors of motion pictures.

Gandhi at his Spinning Wheel (1946) – Margaret Bourke-White

In early 1946, as Indian independence (and the tragic Partition that followed) loomed on the horizon, Life magazine sent star photographer Margaret Bourke-White to photograph India’s leaders, including Mohandas K. Gandhi. Gandhi was living in a communal ashram, and all members were required to spin thread. When Bourne-White asked to photograph Gandhi at his spinning wheel, he encouraged her to learn to spin first. (A photo of Bourke-White with a loom – see below – provides evidence that she followed the suggestion.) The famous photo actually depicts Gandhi not during but shortly after his early morning spinning session, while he is reviewing some documents. Life did not publish the photo with the article it was taken for, but first used it to illustrate a shorter piece later in 1946. It was only the prominent use of the photo in Life’s 1948 spread on Gandhi’s assassination that established its iconic status.

Guerrillero Heroico (1960) – Alberto Korda

On March 4, 1960, the French ship La Coubre exploded in Havana harbor in Cuba under suspicious circumstances, killing nearly 100 people and injuring many more. Cuban President Fidel Castro blamed the American CIA and scheduled a memorial service the next day at Colón Cemetery. Among those attending were Castro’s official photographer, Alberto Korda, and Cuban revolutionary leader Che Guevara, who was then serving as Minister of Industry. Korda was using a Leica M2 camera with a 90 mm lens and Kodak Plus-X pan film to photograph the event. Guevara only came into Korda’s sight for a few seconds, and he snapped two shots of him, one framed by a palm tree and the profile of another mourner. Korda cropped out the framing images to create the timeless portrait known the world over, revealing Guevara’s anger, pain and implacability (see image above). In 1986, photographer José Figueroa suggested printing the original uncropped shot (shown below) as well as the cropped version. The photograph has its own film documentary, Chevolution (2008), and book, Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image (2009), by Michael Casey.

Vietnamese Children after Napalm Attack (1972) – Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut

This photograph, which was taken by Vietnamese-born AP photographer Huỳnh Công “Nick” Út about a year before the end of America’s involvement in the Vietnamese Civil War, put the lie to government claims that American napalm attacks did not affect Vietnamese civilians. The napalm had burned the clothes off the body of the screaming girl, Phan Thị Kim Phúc. After taking the shot, Ut used his media pass to get Kim and the other children admitted into a hospital. Nick and Kim have stayed in touch over the years. The cropped version of the photo shown above, which places Kim in the center, was the one originally published. The cropping eliminated two soldiers and a photojournalist dressed in soldier’s gear engaged in changing his film, as seen in the original uncropped print below.

On 9 lists

The Open Door (c. 1843) – William Henry Fox Talbot

The Open Door is a landmark photo by English photography pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot. Talbot invented the calotype process, in which multiple positive images could be printed from one negative, which eventually replaced daguerreotypes. The Open Door, which appeared in The Pencil of Nature, the first commercially published photography book, is significant for several reasons. First, the lowly subject matter of the photograph – a barn door and a servant’s broom – contrasts significantly with the highbrow subjects that Talbot and others normally aimed their cameras at: monuments, cathedrals and spectacular scenery. The Open Door is a recognition that even the most quotidian subjects may capture the photographer’s eye and offer something new to the viewer. In addition to opening up new subject matter for photographers, The Open Door opened a door to a new aesthetic sensibility. This is perhaps the first photograph in which a setting was deliberately arranged for artistic effect. Talbot has opened the door of the farm building, hung a lantern and propped a broom against the wall. He also appears to have chosen the time of day to enhance the contrast of light and shadow and the view of the window in the back of the room. Instead of treating the camera as a mindless machine simply replicating what happens to be in front of it, Talbot saw the potential of photography as an artistic endeavor, with the conscious input of the artist. As viewers, we appreciate the contrast of light and dark, sun and shadow, indoors and outdoors, and the many textures presented. We also wonder where the sweeper has gone, and when he or she is coming back. Talbot’s photo was a precursor of pictorialism, the late 19th-early 20th century movement that sought to make photography an art (like painting) by emphasizing the conscious manipulations of the artist over the chance effects of ‘straight’ photography.

Soviet soldiers raise USSR flag over Reichstag in Berlin (1945) – Yevgeny Khaldei

As the Second World War in Europe neared its end and Soviet troops entered Berlin, Josef Stalin instructed Tass photographer Yevgeni Khaldei to create an image to rival the American photo of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima. Legend has it that Khaldei flew back to Moscow but could not find any flags, so he ‘borrowed’ three red tablecloths from a government building and had an uncle sew on the hammer and sickle. Back in war-torn Berlin, Khaldei staged flag raisings at the Templehof Airport and the Brandenburg Gate, but neither produced a powerful image. He then turned to the Reichstag building, a symbol for many of Nazi power (even though Hitler saw it as a symbol of the weak republic he replaced and had shut it down in 1933). Soviet soldiers had raised a flag on the Reichstag on April 30, 1945, but it was too late in the day for pictures. In fighting the next day, German troops removed the flag. On May 2, the Soviets gained full control of the building and Khaldei climbed to the top with a flag and three soldiers, where he captured a timeless image of the Nazi defeat. Before the photo was published in a Soviet magazine, Khaldei was ordered to alter the photograph in two ways: he erased the multiple watches on a soldier’s arms (evidence of looting) and added more dramatic smoke in the background.

Vietnamese Monk Self-immolation (1963) – Malcolm Browne

Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem was a Catholic whose repression of the Buddhist majority reached a crescendo with the killing of nine Buddhist protesters during a peace march on May 8, 1963. As a result of the killings, Buddhist monks began to organize protests. AP photographer Malcolm Browne received notice of an important protest to take place on June 11, 1963. When he arrived, he was the only Western journalist present as Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc sat down in a Saigon intersection while other monks poured gasoline on him and set him on fire. Using a cheap Japanese camera called a Petri, Browne shot 10 rolls of film while the monk burned, then had the film sent to AP headquarters. The Pulitzer Prize winning shot above was chosen by AP editors, who then sent it out on the wire, from which newspapers all over the world printed it on June 12, 1963. (Another, somewhat different shot was also published – see below.) Not every paper ran the photo: the New York Times declined to publish Browne’s shot on the grounds that it was too grisly.

Afghan Girl (1985) – Steve McCurry

During the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, a young Pashtun girl’s parents were killed, so she, her brother and grandmother walked many miles to a refugee camp in neighboring Pakistan. In 1984, the girl, then about 12 years old, was attending a makeshift school when American photographer Steve McCurry took her picture for a National Geographic magazine assignment. It was only after McCurry developed the film that he realized the power of the girl’s portrait, with her piercing green eyes looking right into the camera. The photo, titled Afghan Girl, graced the June 1985 cover of National Geographic, and became one of the most popular photos in the magazine’s history. In 2002, after the US invaded Afghanistan and deposed the Taliban, the magazine sent McCurry and a team to try to find the Afghan girl. After many false leads, they found her – now a 30-year old mother of three whose hard life showed on her face and who had no idea that her photograph was famous (see photo below).

On 8 lists

Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) – Man Ray

Man Ray (1890-1976), born Emmanuel Radnitzky, was a modernist American artist who worked in Paris, primarily as a photographer, and whose work was associated with Surrealism and Dada. Le Violon d’Ingres is meant to operate on several levels. It is a semi-nude portrait of famous Paris model Kiki de Montparnasse, with a turban and towel, seen from behind. But Man Ray has painted the f-holes of a violin onto the photograph, then re-photographed it, to imply that Kiki’s seemingly armless torso is actually a musical instrument. The title refers to the painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, known for his nude figures, with their long and winding curves. The phrase “Le Violon d’Ingres” is also a French idiom for ‘hobby’ based on Ingres’s fondness for playing the violin. Thus, the photo implies that, while Ingres’s hobby was playing the violin, Man Ray’s is ‘playing’ Kiki.

Pepper No. 30 (1930) – Edward Weston

In the 1920s, American photographer Edward Weston began photographing what he called ‘still lifes’ – mostly shells, vegetables and fruits. He first photographed a green pepper in 1927, and made 26 pepper photos in 1929. Weston later wrote that peppers had “endless variety in form manifestations [and] extraordinary surface texture” and he admired “the power … suggested in their amazing convolutions.” In early August 1930, Weston tried something new: instead of his usual burlap or muslin background, he placed a pepper just inside the opening of a large tin funnel. The funnel was, he said, “a perfect relief for the pepper” by “adding reflecting light to important contours.” Weston made a six-minute exposure using a Zeiss 21 cm. lens on an Ansco 8 X 10 Commercial View camera. Of all the pepper photographs Weston took, it was Pepper Number 30, with its curves and contours, light and shadows, and even a small blemish at the lower right, that has received the most regard. Random Trivia: Legend has it that after Weston finally obtained the shot he wanted, he cut up the pepper and added it to a salad for dinner with his family.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945) – Joe Rosenthal

The United States invaded the Japanese Pacific island of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945. By February 23, US Armed Forces had captured Mount Suribachi, the highest point on the island, and raised a small American flag there. Soon afterward, the troops were instructed to replace the small flag with a larger one. This time, Associated Press photograph Joe Rosenthal captured the flag raising using a Speed Graphic camera set to a shutter speed of 1/400 sec. Rosenthal had set his camera down to pile some rocks to stand on when he saw the raising begin out of the corner of his eye and quickly took the photo without looking in the viewfinder. The photo shows five Marines and a Navy corpsman raising the flag. Three of the Marines died in fighting over the next few days. The other three flagraisers returned to the US as celebrities to participate in fundraising for the war effort, an experience related in the book and movie Flags of Our Fathers. The image won Rosenthal the Pulitzer Prize and formed the basis for the Marine Corps War Memorial in Washington, D.C., which was sculpted by Felix de Weldon in 1954 (see below).

The Family, Luzzara, Italy (1953) – Paul Strand

After helping to found modernist photography with his formalist, quasi-abstract compositions of lines and shadows in the 1910s, Paul Strand’s interests evolved toward portraiture and the more traditional cultures of Europe. In the 1950s, he moved to France. In 1953, Strand traveled to the town of Luzzara in northern Italy’s Po River valley for several months. While there, he spent time with the Lusettis, a family of tenant farmers. The Family is a portrait of the Lusetti widow matriarch with several of her eight living sons in front of their modest house. Note how all the subjects’ heads are in nearly the same plane but most of the men are not looking at the camera. Also note how the bicycle wheel is echoed in the windows over the door and at the back of the house. Strand took another version of the shot without the man standing in the doorway but this version received more praise.

Earthrise (1968) – William Anders

On December 24, 1968, the Apollo 8 spacecraft was orbiting the Moon with three American astronauts aboard, when one of the men, William Anders, took of photograph of the Earth rising over the moon. Anders used a modified Hasselblad 500 EL with 70 mm Ektachrome film. The blue marble that is our planet appears both beautiful and fragile in the desolation of space. Wilderness photographer Galen Rowell called Earthrise “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” The U.S. Postal Service used a detail of the photo for a 1969 postage stamp.

Vulture Stalking a Child – Sudan Famine (1994) – Kevin Carter

Shortly after arriving in southern Sudan in March 1993 during a famine, South African photographer Kevin Carter observed a hooded vulture standing near a starving Sudanese child, waiting for her to die. Carter took this Pulitzer Prize winning photo of predator and human prey that has become a symbol of the despair and misery of Third World famine. When the photo was taken, the child’s parents had left their daughter to get food from a relief plane that had just landed. The little girl eventually got up and walked away after Carter shooed away the vulture, although no one knows her ultimate fate. Carter was haunted by the event and, despite instructions not to touch famine victims (to avoid spreading disease), he regretted not doing more for the girl. The picture ran in The New York Times on March 26, 1993. While many praised the photo for bringing attention to the famine, some editorials castigated Carter as a heartless journalist who was just ‘another vulture.’ On July 27, 1994, three months after winning the Pulitzer Prize, the 34-year-old Carter, who suffered from depression, committed suicide.

On 7 lists

Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt (1865) – Nadar

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known by his professional name of Nadar, was a French photographer best known for his portraits of the rich and famous. The renowned actress Sarah Bernhardt was one of his most-photographed subjects. While the much-sought-after Nadar left the day-to-day work to his assistants, a visit from someone like Bernhardt brought the great photographer himself out from his backroom office. The photo above comes from an 1865 portrait session, in which Nadar dressed the 23-year-old Bernhardt in classical robes, leaning on a column, suggesting that she transcends time and belongs to the ages. He manages to show his subject’s youthful beauty while giving her a timeless look, bringing out her theatrical essence, but also the vulnerability of a young woman near the beginning of what would be a long career. For a contrasting look, see Nadar’s more contemporary portrait of Bernhardt from one year earlier, where he wraps her in dark velvet and turns her head away from the camera.

Sadie Pfeifer. 48 inches tall. Has worked half a year. Lancaster Cotton Mills, South

Carolina (1908) – Lewis Hine

As the photographer for the US National Child Labor Committee, Lewis Hine’s assignment was to capture in photographs the truth about child labor in the United States in the early years of the 20th Century. He traveled all over the US, documenting children working in factories, mills and mines, as paperboys and in all-night bowling alleys. The photographs were instrumental in the passage of child labor laws. Here, Hine shows a young girl in a tattered dress working in a South Carolina cotton mill. Hine composes the shot so that the huge machines and factory walls dwarf the girl and her co-worker.

Wall Street (1915) – Paul Strand

By 1915, American photographer Paul Strand, like his mentor Alfred Stieglitz, was moving away from pictorialism and towards the modernist mode of straight photography. He also came under the influence of Lewis Hine, who saw photography as a tool of social justice. Wall Street shows the impact of both influences. Strand captures a nearly abstract scene of anonymous workers, dragging long shadows behind them as they rush past a monumental structure – the recently erected J.P. Morgan Trust Company building at 23 Wall Street – that seems to dwarf them. Strand’s formal emphasis on lines and shapes, light and shadow, is very modernist, as is the candid, unposed nature of the shot. But beneath the abstraction is a social message about the way that capitalism turns individual humans into anonymous cogs in the money-making machinery. The dark rectangles in the bank’s facade not only create a dramatic chiaroscuro effect but also loom as caverns that might swallow up the tiny workers passing by, or hide the nefarious doings of the capitalists inside those impenetrable walls.

The Lynching of Young Blacks – Indiana (1930) – Lawrence Beitler

On August 6, 1930, in Marion, Indiana, three young black men – Thomas Shipp, Abram Smith and James Cameron – were arrested and charged with murdering a white man and raping his girlfriend (who later recanted her accusation). The next night, a mob broke into the jail and dragged them out. Cameron was able to escape, but the lynch mob killed the other two men by hanging them from a tree. Lawrence Beitler, a local studio photographer, took a photograph of the hanging men, surrounded by the gleeful mob. Beitler sold thousands of copies of the picture over the next 10 days. When Abel Meeropol saw a copy of the photo in 1937, it inspired him to write the poem “Bitter Fruit”, later adapted into the Billie Holiday song, “Strange Fruit.” James Cameron, who escaped the lynching, became a civil rights activist and director of the Black Holocaust Museum. No one has ever been charged in the deaths of Shipp and Smith.

Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, Place de l’Europe (1932) – Henri Cartier-Bresson

French street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson almost never cropped his photos as a matter of principle, but in this case, he was looking through a hole in a fence that was not quite large enough for the lens of his Leica camera, so he found it necessary to crop the left side of the image, which was blocked by the fence. In other respects, the photograph is the quintessential example of Cartier-Bresson’s philosophy of finding ‘the decisive moment’ when subject and composition come together to create memorable images. Here, we see the puddle-jumper blurred in motion, suspended over water and his own reflection, while a circus poster behind him (also reflected) echoes his jumping stance. The title, which refers to a train station, is echoed by the name on the poster, which contains the English word ‘rail’, and the train-track appearance of the ladder from which the man has jumped. Within the borders of the frame, Cartier-Bresson gives us the sense of a moment frozen in time, yet filled with potentiality.

Portrait of Winston Churchill “The Roaring Lion” (1941) – Yousuf Karsh

The Canadian government hired Turkish-born Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh to photograph British Prime Minister Winston Churchill when he came to Ottawa to speak to the Canadian House of Commons on December 30, 1941, in the depths of World War II. When Churchill arrived, cigar in mouth, he brusquely told Karsh that he had only two minutes to take the picture. Karsh asked Churchill to take the cigar out for the photo, but Churchill refused. In a demonstration of raw courage, Karsh then walked up to Churchill, said, “Forgive me, sir” and pulled the cigar out of his mouth. Karsh went back to the camera to face a belligerent cigar-less Churchill, and snapped the famous portrait that symbolized British defiance of the Nazis and made the cover of Life magazine. Churchill later shook Karsh’s hand and told him, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed”, after which Karsh titled the portrait, The Roaring Lion.

Ruby Shoots Oswald (1963) – Bob Jackson

On November 24, 1963, Dallas Times Herald photographer Bob Jackson was waiting for suspected JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald to be transferred from the city jail to the county jail when a reporter from the paper told him he had been reassigned to cover a press conference at Parkland Hospital, where Gov. John Connally’s wife Nellie was due to speak. Fortunately for photojournalism, Jackson, who had been riding in the motorcade two days before and missed shots of Kennedy’s assassination because he was out of film, disregarded the instructions. A few minutes later, Oswald came out and local nightclub owner Jack Ruby surged toward him with a pistol. Jackson and Dallas Morning News photographer Jack Beers both snapped their shutters. Neither one knew what they had until they went back to their darkrooms and developed the film. Beers got Ruby’s surge, with the rest of the crowd still unaware, but Jackson’s Pulitzer Prize winning photograph, snapped 6/10 sec after Beers’, captured Oswald’s reaction as the bullet hit him and became instantly iconic. The original print, shown below, was cropped considerably to create the familiar image above. Random Trivia: Some Internet trickster has manipulated the photo in an irreverent pop culture parody (either funny or in bad taste, depending on your sensibilities), by adding instruments and morphing the murder into a rock concert, with guitarist Ruby, the sheriff on keyboards and Oswald singing lead vocals.

Tank Man (1989) – Jeff Widener

There are several similar photos of the famous Tiananmen Square Tank Man by different photographers, all taken on June 4, 1989, the morning after the Chinese government had violently suppressed the massive pro-democracy protests in which hundreds of thousands of citizens occupied Beijing’s central square for several weeks in spring 1989. The unidentified man stood in front of the government tanks to stop them from going forward. When the tanks tried to move around him, he would move to block them again. Eventually, someone took the man aside, and the tanks proceeded. AP photographer Jeff Widener was about a half mile away, on the sixth floor of the Beijing Hotel, at the time of the Tank Man’s protest. He used a Nikon FE2 camera with a Nikkor 400mm 5.6 ED IF lens and TC-301 teleconverter and a roll of Fuji 100 ASA color negative film. Photographs of the event by Stuart Franklin and Charlie Cole also received wide attention, as did videos.

On 6 lists

Portrait of Louis Daguerre (1844) – Jean Baptiste Sabatier-Blot

In 1844, when French portrait photographer (and Daguerre’s student) Jean Baptiste Sabatier-Blot took this portrait, Louis Daguerre was world famous for his invention of the first successful photographic process. Daguerre began working on photography with Nicéphore Niépce in 1829 and continued after Niépce’s 1833 death, eventually developing the daguerreotype process, which he announced in 1839. Daguerre gave the rights to his invention to French government in return for granting him a lifetime pension. France then released the process to the world free of any copyrights or restrictions. Daguerreotypes were known for their extreme clarity and fidelity to the subject, but were easily damaged by light or touch and did not produce an image that could be easily duplicated. Despite the invention of the calotype and wet collodion processes, daguerreotypes remained popular with European portrait photographers into the 1850s – even longer in the United States.

Two Ways of Life (1857) – Oscar Gustav Rejlander

Born in Sweden, painter and photographer Oscar Gustav Rejlander spent most of his career in France and England. After starting as a painter, Rejlander became entranced by the possibility of making art with photographs. He became known for allegorical, painting-like photos that often combined more than one image and was an early proponent of the style that became known as pictorialism. His trademark combination photography began when, as a novice photographer, Rejlander had difficulty keeping all the elements of the composition in focus, so he made a separate negative for each element and then printed them together in a complicated process of photomontage. Two Ways of Life was Rejlander’s best known work. Using a composition that relies heavily on Raphael’s The School of Athens, Rejlander depicts a father (or a sage) showing two young brothers a choice between two lifestyles: Virtue on the right and Vice on the left. Perhaps unintentionally, the brother on the side of Vice, with its nude women and lascivious behavior, seems more interested than the brother presented with the more refined pleasures of Virtue. What appears to be a single scene is actually a seamless montage of 32 separate negatives, a fact that allowed Rejlander to reassure his proper Victorian audience that the nude women and the men were never in the same room together. The nudity was controversial nonetheless, and one museum exhibited the photo with a curtain over the left side. Much of the criticism subsided after Queen Victoria purchased one of the few prints as a gift for Prince Albert.

Power House Mechanic Working on Steam Pump (1920) – Lewis Hine

Americans lost interest in child labor after World War I, so photographer Lewis Hine left the National Child Labor Committee and began to work on other projects. Beginning in 1919, he began to create ‘work portraits’, photographs intended to raise the stature of industrial workers. This shift in subject matter also brought about a change in photographic style, from the gritty realism of the child labor images to a more stylized approach, with posed figures and careful lighting that recall in some ways the formulas of Soviet Realism. Here, a worker hunches over in front of a circular machine (which encloses him like a womb), straining his muscles to move the nut with his wrench. He struggles with the machine, yet he seems to become part of it. The message is that there is dignity in hard work.

Omaha Beach, Normandy (1944) – Robert Capa

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, Life magazine photographer Robert Capa arrived at Omaha Beach in Normandy, France along with the invading American troops. As German machine gun fire hit the water around him, he exposed three rolls of film as he photographed the men fighting and dying, then escaped to London on a returning ship. There, an overeager lab technician destroyed most of the precious film; Capa was able to salvage 11 negatives, all of which were significantly blurred. The best of the surviving photos shows an American GI lying on his belly in the surf, grim determination on his face, with the wreckage of war strewn about him. The accidental blurring of the image conveys a sense of agitated movement and the chaotic intensity of the D-Day landings, and it became an iconic portrait of the Normandy invasion.

Atomic Bomb over Hiroshima (1945) – George R. Caron

By August 6, 1945, the Manhattan Project had produced two atomic bombs: Fat Man, a plutonium bomb with an implosion-type detonation mechanism, and Little Boy, a uranium-235 bomb with a gun-type fission mechanism. Both bombs were transported to Tinian Island in the Pacific Ocean and Little Boy was loaded onto a bomber named Enola Gay, which then flew to its primary target, the Japanese city of Hiroshima. At about 8:15 a.m. Japanese time, the crew dropped the bomb from 31,000 feet. It fell for 44 seconds and detonated at 1900 feet, killing 70,000 people immediately and destroying 69% of the city’s buildings. Another 70,000 people died of burns or radiation poisoning in the next five years. The photo of the mushroom cloud was captured by tail gunner Staff Sgt. George Caron, who was situated in the rear of the Enola Gay. Copies of the photo were dropped over Japan in the next days as a warning and invitation to surrender, which would not come until after Fat Boy fell on Nagasaki.

Einstein Sticks His Tongue Out (1951) – Arthur Sasse

It was March 1951 and the paparazzi were hounding Albert Einstein on the night of his 72nd birthday celebration at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. After the birthday banquet, the world-famous physicist walked back to a car with Dr. Frank Aydelotte and his wife, all the while being asked by photographers to smile for the camera. UPI photographer Arthur Sasse waited until Einstein and the Aydelottes were seated in the car to ask for a birthday smile. In response, the Nobel Prize winning genius stuck out his tongue for an instant, then quickly turned away. Quick on the shutter, Sasse got the shot that turned Einstein from a genius to a pop culture icon. Einstein liked the image so much that he cropped out his companions and sent the picture as a greeting card to friends. This cropped version continues to adorn t-shirts and other paraphernalia, reminding us that even geniuses have a sense of humor.

Bolivian Army with the Corpse of Che Guevara (1967) – Freddy Alborta

In 1967, Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara was fighting with Marxist insurgents in Bolivia when the CIA-trained Bolivian army captured and killed him. In a small mountain town they displayed his corpse for the press, including Bolivian photographer Freddy Alborta, whose portrait of Che in death was soon distributed around the world. The Bolivian government’s intent in parading the body before the cameras was to demonstrate their might but the photo, with its resemblance to paintings of the dead Christ, only furthered Che’s legend and made him a martyr to the cause.

5

Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey (1835) – William Henry Fox Talbot

Before Daguerre and his daguerrotypes, there was William Henry Fox Talbot. In 1835, he took a photograph of a latticed window at his Wiltshire home, Lacock Abbey. Setting the camera indoors, which permitted an uninterrupted long exposure, at a point where bright sunlight streamed through the window, led to Talbot’s first successful experiments. Talbot’s process created what we today call negatives, with the darks and lights reversed; the negative above, which is located in the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, is only about an inch square. The next phase, creating a positive print from the negative, was more troublesome. It wasn’t until 1839, about the same time that Daguerre was announcing the daguerreotype process, that Talbot figured out how to create permanent prints from his negatives in what became known as the calotype process. An print made in 1839 from Talbot’s 1835 Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey negative is shown below.

.

.

Still Life: The Artist’s Studio (1837) – Louis Daguerre

The Artist’s Studio is one of Louis Daguerre’s first daguerreotypes and is an early example of pictorialism, in which photographers sought to raise photography to the level of an art by imitating the look, style and genres (in this case, the still life) of the art of painting. The daguerrotype is now in the collection of the Societe Francaise de Photographie in Paris.

Le Stryge (The Vampire) (1853) – Charles Nègre

Photographers and friends, Charles Nègre and Henri Le Secq both loved Paris and Gothic architecture, so it is no surprise that they photographed each other on the parapets of Notre Dame Cathedral overlooking their beloved city. Nègre’s 1853 photo, made using the wet-plate calotype process, was never exhibited in his lifetime, but its value was recognized after his death. The photo has acquired the title Le Stryge (The Vampire), after an 1853 engraving of the same gargoyle by Charles Méryon (see below).

Fading Away (1858) – Henry Peach Robinson

A student of Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, British pictorialist photographer Henry Peach Robinson combined five different negatives to create a single print of the fictional deathbed scene he called Fading Away. The storytelling quality of the photo and the deep sentiment it aroused made it a bestseller for Robinson, who exhibited it at no fewer than five exhibitions in 1858-1859. But the subject matter – a young girl dying of tuberculosis – and the artificiality of the technique raised some criticisms, particularly from those who thought death was not a proper subject for photography. Once again, the royal family saved the day – Prince Albert purchased a copy and issued a standing order for every subsequent composite photo by Robinson.

Tartan Ribbon (1861) – James Clerk Maxwell & Thomas Sutton

James Clerk Maxwell, a Scottish scientist best known for his discovery that light, electricity and magnetism are all forms of the same energy, was also fascinated by the nature of color and in 1861 produced what is believed to be the first color photograph. Working with photographer Thomas Sutton, Maxwell photographed a tartan ribbon (a Scottish emblem) three times, each time with a different color filter (red, green and blue) over the lens. Maxwell and Sutton then developed the three images and projected them onto a screen with three different projectors, each with the same color filter used to take the picture. When brought into focus, the three images formed a full color image. Maxwell presented his discovery as an illustration for a lecture on color he gave at the Royal Institution in London. The Maxwell-Sutton separation process became the basis for most subsequent color photography. The original three plates are now located in a museum in the house where Maxwell was born in Edinburgh.

Portrait of Georges Sand (1864) – Nadar

French portrait photographer Nadar took this photograph of prolific French writer George Sand (born Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin) in 1864, when she was 60 years old. Sand was known for pushing the boundaries of gender identity by smoking and dressing in men’s clothes. Her affair with Frederic Chopin was legendary. The photograph was made using the newly invented woodburytype process.

Yosemite Valley from the Best General View (1866) – Carleton E. Watkins

American photographer Carleton Watkins left his studio in San Francisco several times to photograph the remote and little-explored Yosemite Valley. He carried nearly 2000 pounds of equipment by mule train, including two cameras – one that made stereographs – double shots for viewing in the popular stereoscopes – and the other, a custom-built ‘mammoth’ camera that held glass plate negatives measuring 18 by 22 inches. The photos resulting from Watkins’ first Yosemite trek in 1861 were made into a limited edition book that made its way to the desk of President Lincoln, and likely influenced his decision to set aside the valley as the first protected public land in the U.S. in 1864. On a return trip to Yosemite in 1866, Watkins took this classic shot, which takes in Yosemite Falls (in the center), Bridal Veil Falls, Half Dome, El Capitan and Cathedral Rock. Using a foreground object (here, the tall tree) to contrast with the majestic background was a trademark Watkins technique that would be adopted by Ansel Adams and others.

Mount of the Holy Cross (1873) – William Henry Jackson

In 1873, American photographer William Henry Jackson went to Colorado to find a legendary mountain that displayed a cross of snow. Jackson found the Mount of the Holy Cross in the high Rockies – it was early summer and just enough snow had melted to allow the snow remaining in crossing ravines to create the shape of a Christian cross. Jackson climbed up another mountain to get the best angle and the early morning light and took eight photographs, the best of which is shown above. The photo confirmed the legend. Over the years, Jackson returned to the spot in an attempt to duplicate the image, without success.

Looking down Sacramento Street, San Francisco, April 18, 1906 (1906) – Arnold Genthe

The San Francisco earthquake occurred at just after 5 a.m. on April 18, 1906. Photographer Arnold Genthe’s studio and all the cameras in it were destroyed by falling debris, so he went to a friend’s camera shop the same morning and borrowed a 3A Kodak Special camera and lots of film and began photographing the devastation. The best known shot is one taken on Sacramento Street on Nob Hill, looking down toward the advancing fire. On the right, we see a house whose front has fallen into the street. Up and down the hill, groups of people stand or sit in chairs watching the spectacle.

Spinner in Whitnel Cotton Mill (1908) – Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine’s original caption for the National Child Labor Committee was as follows: “One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She was 51 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. Sometimes works at night. Runs 4 sides – 48 [cents] a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, ‘I don’t remember,’ then added confidentially, ‘I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same.’ Out of 50 employees, there were ten children about her size. Whitnel, North Carolina.”

Blind Woman, New York (1916) – Paul Strand

In 1916, Paul Strand took a number of candid street portraits using a handheld camera with a special lens that allowed him to point the camera in one direction while taking the photograph at a ninety-degree angle. In this case, the elaborate ruse was pointless, as the subject could not see either Strand’s camera or the image he created. As one commentator noted, Strand manages to capture the “misery and endurance, struggle and degradation” in this human being, who has a license to beg and a sign that reduces her to a single attribute. (In fact, many publications give this photo the one-word title, “Blind.”) Alfred Stieglitz published Strand’s image in his magazine Camera Work in 1917 as an example of the new modernism, which integrated social documentation with boldly simplified formal compositions.

Portrait of My Mother (1924) – Alexander Rodchenko

Russian photographer and montagist Alexander Rodchenko’s mother had just recently learned to read when her son made her portrait in 1924. His original shot (see below) shows her holding up her glasses to decipher a Soviet magazine. In the darkroom, however, Rodchenko rethought the composition, and focused on his mother’s intensely-concentrating heroic/tragic face, her working class hands and the strange swirl of her glasses. Gone are the contextual magazine and walls and what remains is a more dramatic, more universal image.

Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company (1927)

– Charles Sheeler

It wasn’t long after the birth of photography that big business discovered ways to use the medium to increase profits and improve its image. The image above was created by Charles Sheeler as an assignment for an advertising company working for Ford Motor Company. Empty of human life, the scene depicts the machinery and metallic structures of a modern factory, with soaring smokestacks reaching heavenward, as a kind of technological utopia, as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s commentator points out. Sheeler’s lens finds harmony and dynamic energy in what to some eyes might be a jumble of mundane industrial structures. Ford used the image in many of its publications, but Criss-Crossed Conveyors rose above its advertising origins to become an example of photography as art.

Pastry Cook, Cologne (1928) – August Sander

German portrait photographer August Sander did not believe in gimmicks. His goal was to create social documents that identified the people of Germany according to their social class, economic status and occupation. To achieve this goal, Sander used a large format camera and photographed his subjects full length and facing the camera. He liked to show working people with the tools of their trade, but he also narrowed the depth of field to avoid distracting background details. Even without the title, we can easily identify the eponymous Pastry Cook of Sander’s 1928 portrait by his costume, whisk and bowl. Sander’s eye has caught the imposing figure with an expression that hovers between the neutrality of the humble tradesman “just doing my job” and the pride taken in job well done. Pastry Cook was included in Sander’s 1929 book Face of our Time, which sold well for years until the Nazis removed it from the shelves on the grounds that it depicted too many non-Aryan faces.

Lunch Atop a Skyscraper (1932) – Charles C. Ebbets (?)

The 1932 photograph known as Lunch Atop a Skyscraper is not what it seems. It does show 11 construction workers of varying ethnic backgrounds – some of them immigrants – sitting on a beam on the 69th floor of the nearly finished RCA building at 30 Rockefeller Center in New York. And yes, they are having lunch. But historians have revealed that this was no candid shot, but a carefully-planned publicity stunt designed to get positive press coverage for the city’s latest skyscraper. According to a letter written by one of the workers at the time, there was a floor just below the beam but outside the frame, reducing the risk considerably. The picture ran in the New York Herald American but Charles Ebbets was not identified as the photographer until 2003. More recently, however, Corbis, which owns the photo, has labeled the photographer as ‘unknown.’

At the Time of the Louisville Flood (1937) – Margaret Bourke-White

In January 1937, the Ohio River flooded, killing nearly 400 people and leave almost a million people homeless. Life magazine sent Margaret Bourke-White to Louisville, Kentucky to document the tragedy. Her image of African-American families lined up for food in front of a painfully ironic billboard was published in the February 15, 1937 issue of Life. The billboard was part of an anti-New Deal campaign by the National Association of Manufacturers. Over the years, the photograph has become a symbol not just of the Louisville flood, but of the Great Depression generally.

Explosion of the Hindenburg (1937) – Sam Shere

The German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg had crossed the Atlantic and was attempting to dock at a mooring mast at the Lakehurst Naval Station in New Jersey at about 7:25 p.m. on May 6, 1937 when it caught fire and burned to the ground, killing 35 of the 97 people on board, and one person on the ground. Numerous journalists were present, including radio announcer Herbert “Oh, the humanity!” Morrison, newsreel cameramen and several photojournalists. The iconic photograph of the initial burst of flaming hydrogen was taken by Sam Shere, using a Speed Graphic camera. According to Shere, the event happened so fast, he had to ‘shoot from the hip’, squeezing the shutter even before he got the camera to his eye. As a result of the Hindenburg disaster and the publicity surrounding it, the public lost its faith in rigid airships and the entire passenger airship industry, leaving only the Goodyear blimp and its kin as reminders of a bygone era.

Sunday on the Banks of the River Marne (1938) – Henri Cartier-Bresson

In 1936, the progressive French government passed a law giving French workers two weeks of paid vacation every year, a fact that gives Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photo of two couples picnicking at the riverside a political subtext. Even though we see only part of one of the faces, there is an intimacy to the photograph, a sense that may be enhanced by Cartier-Bresson’s decision to eliminate the horizon line and the opposite bank of the river from the frame.

The Tetons and the Snake River (1942) – Ansel Adams

In 1941, the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service hired American landscape and nature photographer Ansel Adams to photograph America’s national parks, Indian reservations and other federal lands to decorate the Interior Department’s new headquarters with large prints. Using large format cameras and paying close attention to darkroom techniques, Adams captured the drama of the natural landscapes in the American West. His photo of the Snake River winding through a valley with the Tetons towering in the background was taken in Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming. It is one of the photographs included in the Voyager spacecraft for viewing by any extraterrestrials it may encounter.

Buchenwald Victims (1945) – Margaret Bourke-White

American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White joined General Patton’s Third Army in April 1945 when it liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp in Weimar, Germany. Many of Bourke-White’s photos were published in a Life magazine article, but the photo of haunted survivors standing against a barbed-wire fence staring at their rescuers was not seen until 1960, when Life presented it as part of a retrospective issue. Another famous photo from the same time and place shows German citizens forced by General Patton to tour the prison and view the piles of corpses.

Atomic Bomb over Nagasaki (1945) – Charles Levy

By August 6, 1945, the Manhattan Project had produced two atomic bombs: Fat Man, a plutonium bomb with an implosion-type detonation mechanism, and Little Boy, a uranium-235 bomb with a gun-type fission mechanism. Both bombs were transported to Tinian Island in the Pacific Ocean. Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. On August 9, a bomber named Bocks Car dropped Fat Man over Nagasaki, its secondary target, causing significant destruction and deaths, although a row of hills protected much of the city from destruction. Using a 5X4 camera, Lt. Charles Levy took 16 photographs of the Nagasaki mushroom cloud from the transparent nose of one of the other B-29 bombers that made the run.

Dali Atomicus (1948) – Philippe Halsman

Latvian-born American photographer Philippe Halsman had been collaborating with Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali since 1941, but their most famous production is Dali Atomicus, from 1948. The genesis of the photo was the recent scientific discovery that, because atoms consisted of electrons suspended in orbit around the nucleus, all solid matter was actually suspended in space. Dali began a painting on the theme, Leda Atomica, which can be seen on an easel at the far right, and Dali and Halsman collaborated on a portrait of suspended reality. (Although some have identified Dali Atomicus as one of Halsman’s famous jumping photos, it actually precedes Halsman’s adoption of that technique – here the jumping is incidental to the notion of being suspended.) The photo shoot took 28 tries over six hours. When Halsman finally got the shot he wanted, he retouched it to insert a painting on Dali’s easel and eliminate an assistant’s hand holding up a chair and wires holding up other articles (see unretouched version below). The photo was published in a two-page spread in Life magazine.

Death Watch (from Spanish Village) (1951) – W. Eugene Smith

In 1951, Life magazine sent American photographer W. Eugene Smith to the Spanish village of Deleitosa, population 2,300, which is situated in the Estramadura in western Spain. Smith’s photo essay highlights numerous aspects of daily life for the poorest subjects of Franco’s Fascist regime, including a traditional ‘death watch’, a type of wake for a deceased elder of the community. Included among the watchers are the man’s wife, daughter, granddaughter and friends. Another popular image from the Spanish Village series is Guardia Civil, shown below.

Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, Minamata, Japan (1972) – W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith and his wife moved to Minimata, Japan in 1971 to bring attention to the victims of Minimata disease, which was caused by mercury poisoning from a nearby manufacturer. Smith took many graphic photos, some of which were published, but he decided he needed a shot with more symbolic value. He discussed the idea with Ryoko Uemura, whose daughter Tomoko was afflicted. She agreed to allow Smith to photograph Tomoko’s paralyzed body and suggested the bath as a setting. The resulting photo, which was the centerpiece of an article in Life magazine, brought Minimata disease to the world’s attention and helped pressure the polluting company to compensate victims. In 1997, Smith’s widow gave the copyright for the photo to Tomoko’s parents (Tomoko died in 1977 at age 21) and the family has chosen not to allow further distribution of the image (although it is widely available on the Internet).

Footprint on the Moon (1969) – Buzz Aldrin

One of the tasks given to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, the first men to walk on the Earth’s moon, was to study the lunar soil (called regolith) in part to determine what acts the astronauts could perform safely while on the lunar surface. As part of this soil mechanics investigation, Buzz Aldrin took a photograph of the lunar surface, then he stepped on the spot with his boot and took a picture of the resulting footprint. Aldrin’s experiment took place on July 20, 1969, about one hour after Armstrong first set foot on the moon’s surface. The experiment gave scientists information about the behavior of the regolith when compressed by a heavy object. Once made public, the photo of Aldrin’s bootprint took on weightier significance as a symbol of man’s foothold on a new frontier and the permanent mark that humans had made on a celestial body other than Earth.

Buzz Aldrin on the Moon (1969) – Neil Armstrong

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin stands on the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. The photographer is Neil Armstrong, who managed to capture his reflection and that of the lunar module in Aldrin’s visor. The photograph had worldwide significance as it showed, for the first time, a man walking on the moon.

Kent State Massacre (1970) – John Filo

Kent State University journalism student John Filo took this May 4, 1970 photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, a 14-year-old runaway, as she knelt over the body of Kent State University student Jeffrey Miller, who had just been fatally shot by the Ohio National Guard. The Guard had been sent to quell student protests against the Vietnam War, and in particular the bombing of Cambodia, which President Nixon had announced on April 30, 1970. Three other students were killed and nine were injured, including one who was permanently paralyzed. The shootings led to a nationwide student strike involving four million students and contributed to turning public opinion against the war. Filo, who was working part-time at a local newspaper, used a Nikkormat camera with Tri X film at 1/500 sec. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his iconic anti-war image.

Fire Escape Collapse (Fire on Marlborough Street) (1975) – Stanley J. Forman

Stanley Forman was a photographer for the Boston Herald American in July 1975 when he took this controversial photo of a fire rescue turned tragic. Diana Bryant, age 19, and her two-year-old goddaughter Tiare Jones were standing on the fire escape ladder outside their burning apartment as a firefighter approached to save them. Forman stood on the fire truck and photographed the dramatic scene when the fire escape suddenly gave way, sending Bryant and Jones tumbling to the ground. Miraculously, the two-year-old survived, but her godmother died from her injuries. The photo, which won Forman a Pulitzer Prize, is credited with motivating the state to toughen building codes for fire escapes.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono (1980) – Annie Leibowitz

American photographer Annie Leibovitz was working for Rolling Stone magazine in December 1980 when she received an assignment to photograph John Lennon for the cover. Lennon had just released a new album, Double Fantasy, his first in five years. Leibovitz suggested a portrait of John and his wife Yoko Ono, similar to the one on the cover of the new album, but in the nude. Yoko balked at complete nudity, so Leibovitz had a nude John pose with a fully-clothed Yoko. Leibovitz captured John’s touching fetal wraparound with an instant camera. Both subjects felt that the photo captured their relationship exactly, Leibovitz recalled. The photograph took on additional significance when, just hours after the photo session, Lennon was shot and killed by a demented fan. Rolling Stone printed a somewhat altered version of the photograph on the cover of its January 1981 issue (see below).

4

Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840) – Hippolyte Bayard

French photography pioneer Hippolyte Bayard invented a photographic process called direct positive printing, and, in 1839, became the first photographer to give a public exhibition of his work, but his most famous photograph, Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man, is a protest against what he felt was a lack of respect for his accomplishments. In the photo, Bayard presents himself as a victim of suicide by drowning. The staged scene symbolized his reaction to the French Academy of Sciences, which bypassed Bayard in favor of Louis Daguerre, a friend of the Academy’s director, in designating the inventor of photography. Bayard’s caption read in part, “The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. … The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself….”

Portrait of William Henry Fox Talbot (c. 1844) – Antoine Claudet

There is more than a little irony in the fact that the best surviving portrait of William Henry Fox Talbot, inventor of the calotype photographic process, is a daguerrotype, made using the technology of his arch-rival, Louis Daguerre. French photographer Antoine Claudet, a student of Daguerre, had a portrait studio in London and it was there that Talbot came to have several daguerrotypes made in about 1844. Talbot would have the last laugh, however, as his calotype process, which allowed multiple prints from a single negative, would eventually win out over the non-reproducible daguerrotype.

Fire at Ames Mill, Oswego, NY (1853) – George N. Barnard

American photographer George Barnard owned a studio in Oswego, New York when he took this photograph of a fire at the Ames Mills, one of the earliest examples of spot news photojournalism. Barnard hand-tinted the original daguerreotype, using crimson pigment for the flames (see below). It would take nearly 50 more years until newspapers and magazines could easily print photographs in their publications using the half-tone process. In the mean time, however, journalists continued to use the new medium. In lieu of printing the actual photograph, an artist would make an engraving of the image and a printer would then make a print from the engraving that could be inserted into any form of print media.

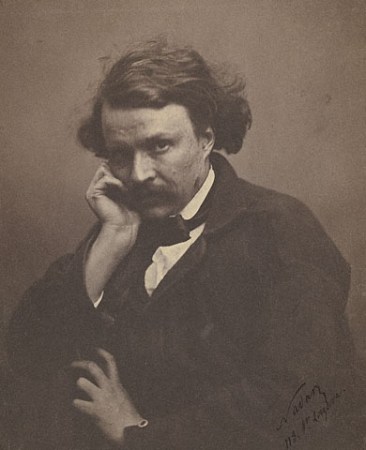

Self-Portrait of Nadar (1855) – Nadar

Gaspard-Felix Tournachon, known professionally as Nadar, was a newspaper caricaturist in 1853 when he discovered photography. In 1855, Nadar opened a studio, where many artists and other well-known figures from France and elsewhere came to have their portraits made. Nadar made numerous self-portraits, both to create a public image of himself as an artist and also to experiment with poses, lighting and other techniques. This Self-Portrait is from about the time he opened his studio. In addition to making portraits, Nadar was a pioneer in lighting dark settings and was the first photographer to take aerial photos, using a hot-air balloon.

Portrait of Sir John Herschel (1867) – Julia Margaret Cameron

To pioneering female photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, Sir John Herschel was not just an illustrious scientist and photography innovator in his twilight years – he was also a good friend. Cameron, who took up photography relatively late in life after receiving a camera as a gift, was known for breaking the rules of portraiture. Instead of cluttering the space with faux classical columns, books, or symbols of the subject’s profession, Cameron chose to arrange the lighting carefully (here, from the right side) and use emotional truth as a guide for focus and pose, avoiding perfect sharpness that accentuates every detail. The result is a Gestalt instead of a collection of attributes; it is a truly human portrait – no distractions and full of life.

Communards in their Coffins (1871) – André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri

Also known by the more prosaic title Dead Communards, this image depicts 12 men who had participated in the failed 1871 Paris Commune uprising, were arrested and executed, then placed in shabby wooden coffins and unmercifully photographed. Each one has a number placed on his chest, but there is no reason or rhyme to this apparent attempt at efficiency – two ‘4’s, no ’12’? It is not clear whether the photographer is seeking merely to document the dead, perhaps at the government’s behest, or whether he intends some political commentary about the cruelty of those who put down the revolt or the price one pays for rebellion. For reasons that are not clear to me, Amazon.com offers a mug with this image printed on it.

Ancient Ruins in the Canyon de Chelly (1873) – Timothy O’Sullivan

American photographer Timothy O’Sullivan was working for George Montague Wheeler’s surveying team of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers when he photographed the White House ruins in Canyon de Chelly in what what then New Mexico Territory and is now in the state of Arizona. O’Sullivan emphasizes the vast striated cliffs, which dwarf the remains of an Anasazi pueblo and serve as a substitute sky over the man-made dwellings.

The Crawlers (from Street Life in London) (1877) – John Thomson

After many years of travel in the Far East, British photographer John Thomson settled in London where in 1876 he embarked on a collaborative project with journalist Adolphe Smith. Together, they published a monthly magazine called Street Life in London, in which Thomson’s photos (made using the woodburytype process) and Smith’s text documented the lives of the city’s desperate poor. The magazine ran from 1876-1877, after which Thomson and Smith published a book of the same name in 1878. In the most well-known of the Street Life photos, an older woman sits on the steps of a workhouse, caring for the child of a woman who has managed to find some work. In return, the woman received some scraps of food. She and others were called crawlers because they no longer had the strength to beg.

The Terminal, New York (1892) – Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz had recently returned from several years in Europe when he found himself in front of the New York post office where two different streetcar lines terminated. The winter scene of steaming horses and their drivers restIng at the end of the line expressed Stieglitz’s sense of being a stranger in his hometown. Stylistically, the photo shares much with pictorialism, but the candid urban setting (and Stieglitz’s use of a 4 X 5 camera, which was much more mobile than the usual tripod-bound 8 X 10) prefigured the straight photography movement of the 20th Century.

The Flatiron Building, NYC (1905) – Edward Steichen

One of the first skyscrapers in Manhattan, the 22-story Flatiron Building opened in 1902 and immediately became a magnet for photographers. Pictorialist photographer Edward Steichen, born in Luxembourg but working in the US, chose to take his Flatiron portrait at twilight in winter, with bare tree branches and horse carriages in silhouette, to create the hazy sense of a painting. Steichen experimented with color by adding dyes in the production process – he used three separate dyes, each one to reflect a different aspect of the growing darkness of twilight, to create three original prints from a single negative.

Playground in Tenement Alley (1909) – Lewis Hine

While working for the National Child Labor Committee, American photographer Lewis Hine not only documented children at work but also at play, as in this photo of a ball game in a crowded alley between two sets of tenement apartments in Boston, beneath drying laundry. The photograph was useful in promoting the building of playgrounds and parks for young children in the inner cities.

Avenue des Gobelins (1925) – Eugène Atget

The sign over the Paris studio of French photographer Eugène Atget read ‘Documents for Artists’, and when avant-garde artist Man Ray suggested that Atget was making Surrealist photos, Atget insisted that he was simply documenting the people and places of Paris and its environs. Atget avoided the obvious – for example, he never pointed his camera lens at that postcard favorite, the Eiffel Tower. Toward the end of his life, Atget became fascinated with shop windows. He appreciated the theatricality of the medium, particularly mannequins (and the confusion of human clerks with non-humans dressed the same way, as seen in 1925’s Avenue des Gobelins). He also enjoyed the reflective quality of the glass windows, which allowed him to contrast the old buildings with new fashion and place the objects of the display in unfamiliar surroundings, here the headquarters of the famous Gobelins tapestry manufacturer directly across the street from the storefront. Atget also printed a second photograph of the same window display from a different angle (see below).

Satiric Dancer, Paris (1926) – André Kertész

Hungarian photographer Andre Kertesz came to Paris in the 1920s to join the thriving Modernist movement there. Satiric Dancer, made in Paris in 1926, includes the participation of two other Hungarian émigrés: István Beöthy provided both the setting – his studio – and the sculpture on the left; dancer and cabaret performer Magda Förstner was the model, drawing her inspiration from the modernist statue to adopt a fetching pose.

Madrid (1933) – Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson bought his first Leica camera in Marseilles in 1932 and it is from that point that he dates the beginning of his career as as photographer. He liked the Leica because it was small and because he could bring it out quickly to get a shot. To draw even less attention to himself, Cartier-Bresson wrapped the shiny silver body of the camera with disguising black tape. He never used a flash, which he felt was impolite, and composed within the camera so that he almost never had to crop. Although he is known for being the photographer of “the decisive moment’, that phrase was borrowed from another. Cartier-Bresson perhaps best expressed his philosophy when he said, “To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.” Madrid, 1933 (or simply Madrid) brings together an unusual setting – a massive white wall with tiny windows – and a world of children, one of whom is moving forward, while a lone adult seems out of place. We don’t know exactly what is going on with the children in the foreground – are they playing a game? – but the picture conveys a sense that an event of significance (at least to the children) is occurring.

Loch Ness Monster (1934) – Ian Wetherell