This is part one of a chronological list of the best photographs of all time. I created the list by collecting over 22 lists with titles like The Best Photography of All Time, The Greatest Photographs Ever, The Most Important Photos, The Most Iconic Photos, The Most Influential Photos from websites and books (including several history of photography books). In order to diversify the list, I also collected lists of the best photographs in particular genres, such as photojournalism, street photography, fashion photography, portraiture, nature and landscape photography and art photography. I then compiled all the lists into one meta-list to determine which photos were on the most lists. The most-listed photo was on 22 of the lists I found. The list below (Part I) includes every photograph that was on at least two of the original source lists, in chronological order, covering the period 1826-1945. For 1945-Present, see Part II here. Each entry includes the number of lists the photo is on, the title (note that many photographs have multiple titles – I have tried to mention alternate titles in the text), the date (usually the date of the exposure, but sometimes the date of the print) and the photographer’s name. A short essay with additional salient information, such as the photographic equipment used, follows in most cases.

A few warnings: (1) Some of the photos contained in these lists depict death and other tragic situations and may be disturbing. (2) Nudity is a fairly common theme in art and fashion photography. I find some of the photographers’ depictions of women to be objectifying and misogynistic, but you be the judge. (3) Some of the more recent photos are still under copyright, so please have respect for the photographers’ legal rights – I have added links to purchase prints in some cases. I believe my use of these lower resolution images falls under the doctrine of fair use and also serves an educational purpose.

For a list of photographs on three or more of the original source lists, organized with the most-listed (“best”) photos first, go to Best Photography of All Time – The Critics’ Picks. For a chronological list of the best photographers and their best photos, including portraits of the photographers, go here.

View from the Window at Le Gras (1826) – Nicéphore Niépce (on 14 lists)

This view from the window of French inventor Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) is believed to be the first permanent photograph ever made. The process Niépce called heliography involved setting up a camera obscura in the window of his home in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes and focusing the image onto a pewter plate measuring 6.4 inches by 8 inches that he covered with bitumen. After an exposure of at least eight hours (an inference based on the sunlight illuminating both sides of the street), the bitumen hardened in the brightly lit areas, and Niépce washed away the bitumen in the dark areas with oil of lavender mixed with white petroleum. Unlike prior attempts to capture the images created by the camera obscura, the resulting photograph was permanent, although the image was only visible when the pewter plate was held at an angle. The plate disappeared about 1905 but was discovered by German historian Helmut Gernsheim in 1952. Gernsheim made a modern photographic copy (damaging the original in the process) and then heavily retouched it to create the image shown above. The original heliograph plate (shown below) is now at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. (c) Gernsheim Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey (1835) – William Henry Fox Talbot (on 5 lists)

Although French inventor Louis Daguerre is generally credited with developing the first successful form of photography, some credit must also go to Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), some of whose experiments preceded Daguerre’s. In 1835, Talbot took a photograph of a Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey, his Wiltshire home. He achieved this first success by setting the camera indoors, which permitted an uninterrupted long exposure at a point where bright sunlight streamed through the window. Talbot’s process created what we today call a negative, with the darks and lights reversed. The negative above, which is located in the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, is only about an inch square. The next phase, creating a positive print from the negative, was more troublesome. It wasn’t until 1839, about the same time that Daguerre was announcing his daguerreotype process, that Talbot invented the calotype process for creating permanent prints from his negatives. A print Talbot made in 1839 from the Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey negative is shown below. (c) National Museum of Photography.

Still Life: The Artist’s Studio (1837) – Louis Daguerre (on 5 lists)

Still Life: The Artist’s Studio is one of the earliest images produced by French photography pioneer Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) using the daguerreotype photographic process, which he developed after the death of his mentor and collaborator Nicéphore Niépce. The subject matter – an arrangement of various objets d’art into a still life – indicates an early example of the desire to treat photography not just as a means of documenting reality but as an art similar to painting, another two-dimensional art form. Daguerre uses what appears to be natural light coming from the side, as well as light reflected in a mirror. After perfecting the process during 1837-1838, Daguerre announced his discovery in general terms to a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Arts on January 7, 1839, with a public announcement following in August of that year. The original daguerreotype is now in the collection of the Societe Francaise de Photographie in Paris. Public domain.

Boulevard du Temple, Paris (1838) – Louis Daguerre (on 11 lists)

The most famous early image by French photography pioneer Louis Daguerre is this 1838 daguerreotype of the Boulevard du Temple, a busy Paris street. It is not only one of the first photographs but is also probably the first time the new medium captured the image of a human being. The daguerreotype process involved coating a thin silver-plated copper sheet with light-sensitive silver iodide and then exposing the plate in the camera. At first, exposure times were ten minutes or more, but over time, Daguerre was able to reduce the time to a few seconds. Daugerrotypes were known for their extremely detailed and realistic images, in contrast to the grainy and fuzzy pictures resulting from other early photographic processes. Drawbacks of the process were that multiple prints could not be made from an exposure, and the images degraded by contact with air or by any scratching or friction. Boulevard du Temple required a 10-minute exposure, which means that most pedestrians and carriages did not stay still long enough to be recorded, creating the illusion of a ghostly barren thoroughfare. The exception, in the lower left, is the man getting his shoes shined, who stood still long enough to register on film and in history as the first photographed human (see detail of image below). The original daguerreotype is located in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, Germany. Public domain.

Self-Portrait (1839) – Robert Cornelius (on 2 lists)

In October 1839, Robert Cornelius (1809-1893), an amateur chemist from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, created what is believed to be the earliest surviving photographic self-portrait (what would today be called a ‘selfie’). Using the recently-announced daguerreotype process, Cornelius made a camera from a box with a opera-glass lens and set it up in the yard behind his family’s lamp and chandelier store. He uncovered the lens and ran to a chair he had set up, sat motionless for a minute, then ran back to end the exposure, which recorded a man with unkempt hair staring suspiciously to his right. The original daguerreotype is now in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. For more information, see “Photographic Material,” by Carol Johnson, in Gathering History: the Marian S. Carson Collection of Americana (1999). Public domain.

Self Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840) – Hippolyte Bayard (on 4 lists)

French photography pioneer Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887) invented a photographic process called direct positive printing, and, in 1839, became the first photographer to give a public exhibition of his work, but his most famous photograph, Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man, is a protest against what he felt was a lack of respect for his accomplishments. In the photo, Bayard presents himself as a victim of suicide by drowning. The staged scene symbolized his reaction to the French Academy of Sciences, which bypassed Bayard’s work in favor of Daguerre’s daguerreotype process when designating the inventor of photography. Bayard’s caption read in part, “The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. … The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself….” It must have been some consolation when, in 1842, the Societe d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale gave Bayard a prize of 3000 francs for his contributions to photography.

The Open Door (from The Pencil of Nature) (c. 1843) – William Henry Fox Talbot (on 9 lists)

The Open Door is a landmark photo by William Henry Fox Talbot, inventor of the calotype process, which (unlike daguerreotypes) allowed multiple positive images to be printed from a negative. The Open Door appeared in The Pencil of Nature, the first commercially published photography book. It is significant for several reasons. First, the lowly subject matter of the photograph – a barn door and a servant’s broom – contrasts significantly with the monuments, cathedrals, famous people and spectacular scenery that photographers normally aimed their cameras at. The Open Door recognizes that the most quotidian subjects may capture the photographer’s eye and offer something new to the perceptive viewer. In addition to providing new subject matter for photographers, The Open Door opened a door to a new aesthetic sensibility. This is an early example of a photograph in which a setting was deliberately arranged for artistic effect. Talbot has opened the door of the farm building (allowing us to see through the window on the back wall), hung a lantern and propped a broom against the wall. He also appears to have chosen the time of day to enhance the contrast of light and shadow. Instead of treating the camera as a mindless machine simply replicating what happens to be in front of it, Talbot saw the potential of photography as an artistic endeavor, with the conscious input of the artist. As viewers, we appreciate the contrast of light and dark, sun and shadow, indoors and outdoors, the many textures presented, and the hint of a narrative. Talbot’s photo was a precursor of pictorialism, the late 19th-early 20th century movement that sought to make photography an art (like painting) by emphasizing the conscious manipulations of the artist over the chance effects of ‘straight’ photography. Public domain.

Portrait of Louis Daguerre (1844) – Jean Baptiste Sabatier-Blot (on 6 lists)

In 1844, when French portrait photographer (and Daguerre’s student) Jean Baptiste Sabatier-Blot (1801-1881) took this portrait, Louis Daguerre was world famous for his invention of the first successful photographic process. After announcing his discovery in 1839, Daguerre gave the rights to the French government in return for a lifetime pension. France then released the process to the world free of any copyrights or restrictions. Daguerreotypes were known for their extreme clarity and fidelity to the subject, but were easily damaged by light or touch and produced an image that could not be easily duplicated. Despite the invention of the calotype and wet collodion processes, daguerreotypes remained popular with European portrait photographers into the 1850s – even longer in the United States. The original of this daguerreotype is now at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester, NY. Public domain.

Portrait of William Henry Fox Talbot (c. 1844) – Antoine Claudet (on 4 lists)

It is more than a little ironic that the best surviving portrait of William Henry Fox Talbot, inventor of the calotype photographic process, is a daguerreotype, made using the technology of his arch-rival, Louis Daguerre. French photographer Antoine Claudet (1797-1867), a student of Daguerre, had a portrait studio in London and it was there that Talbot came to have several daguerreotypes made in about 1844. Talbot would have the last laugh, however, as his calotype process, which allowed multiple prints from a single negative, would eventually win out over the non-reproducible daguerreotype. Public domain.

A Newhaven Fisherman and Three Boys (1845) – David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson (on 2 lists)

Scotsmen David Octavius Hill (1802-1870), a painter, and Robert Adamson (1821-1848), an engineer, teamed up in the 1840s to document life in their beloved Scotland using the new medium of photography. The photograph above, made using Talbot’s calotype process, comes from a series entitled The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth, which documented the inhabitants of a fishing village near Edinburgh. According to the curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the 130-image series “constitutes the first sustained use of photographs for a social documentary project.” Salted paper prints of the image may be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Edinburgh Libraries.

The Misses Binny and Miss Monroe (1845) – David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson (on 2 lists)

The photographic partnership of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson ended in 1848, less than four years after it had begun, due to Adamson’s untimely death. During their brief time together, Hill and Adamson made an estimated 3000 calotype photographs, most of them portraits of Scottish men and women. Little is known about the two Misses Binny and their companion Miss Monroe except what can be seen here. A print of this enduring triple portrait is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Public domain.

Portrait of Mother Albers, The Family Vegetable Woman (1840s) – Carl Ferdinand Stelzner (on 2 lists)

In 1842, successful German painter Carl Ferdinand Stelzner (1805-1894) left painting forever to dedicate himself to the new medium of photography. He and Hermann Biow opened a studio in Hamburg that year and began producing daguerreotypes, although the partnership ended only a year later, forcing Stelzner to open his own studio. It was there that he made a daguerreotype of Mother Albers, the Family Vegetable Woman, surrounded by the implements of her trade. The result was one of the earliest occupational portraits in the history of photography. In the early 20th Century, German photographer August Sander would continue the tradition with his portraits of individuals representing the various occupations. The original daguerreotype is located in the Museum for Kunst and Gerwerbe in Hamburg. Public domain.

Portrait of Alexander von Humboldt (1847) – Hermann Biow (on 3 lists)

Alexander von Humboldt was a famous scientist and explorer, best known for his discoveries during travels in South America between 1799 and 1804. His five-volume work Kosmos (1845), sought to unify the various branches of scientific knowledge. In 1847, von Humboldt sat for this daguerreotype portrait by Hermann Biow (1804-1850), an early German photographer with studios in Altona and Hamburg.

Le Stryge (The Vampire) (1853) – Charles Nègre (on 5 lists)

Photographers and friends, Charles Nègre (1820-1880) and Henri Le Secq both loved Paris and Gothic architecture, so it is no surprise that they photographed each other on the parapets of Notre Dame Cathedral overlooking their beloved city. Nègre’s 1853 photo, made using the wet-plate calotype process, was never exhibited in his lifetime, but its value was recognized after his death. The photo has acquired the title Le Stryge (The Vampire), after an 1853 engraving of the same gargoyle by Charles Méryon (see below). A salted paper print of this image is located in the collection of the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. Public domain.

Fire at Ames Mill, Oswego, NY (1853) – George N. Barnard (on 4 lists)

American photographer George Barnard (1819-1902) owned a studio in Oswego, New York when he made this daguerreotype of a Fire at Ames Mill, one of the earliest examples of spot news photojournalism in the US. (Images of an 1842 Hamburg fire made by Hermann Biow and others are probably the earliest examples of photo reportage worldwide.) Barnard hand-tinted the original daguerreotype, using crimson pigment for the flames. It would take nearly 50 more years until newspapers and magazines could easily print photographs in their publications using the half-tone process. Despite the limitations of technology, photographs still made their way into print, albeit indirectly. Unable to print photographs, newspaper and magazine publishers hired artists to make engraving of photographic images; a printer then made a print from the engraving that could be inserted into any form of print media. (A print from an engraving of a daguerreotype of the 1842 Hamburg fire published in the Illustrated London News is shown below.) George Barnard went on to photograph the U.S. Civil War, particularly Sherman’s march through Georgia, for Matthew Brady.

Pierrot the Photographer (1854-1855) – Nadar (on 2 lists)

Pierrot was a stock character of the French comic theater traditionally played by a mime. The most famous Pierrot was Baptiste Deburau, whose son Charles Deburau had followed in his father’s footsteps. When the French portrait photographer known as Nadar (the professional name of Gaspard-Felix Tournachon (1820-1910)) was looking for an attention-getting series of photographs to boost his recognition and business, he decided to to create a series of images featuring Deburau fils as Pierrot and present them the Universal Exhibition of 1855. The first and most famous of the series is Pierrot the Photographer (also known as The Mime Deburau with a Camera). In a role reversal that recalls the plot twists of the commedia dell’arte, Deburau plays the photographer while, presumably, Nadar is the subject. Pierrot mimics the photographer’s actions: motioning his subject to look at the camera lens, not him, and at the same time pretending to remove a plate from the camera itself. The Pierrot series won a gold medal and much recognition for Nadar’s fledgling studio. A salted paper print of the image is in the collection of the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. Public domain.

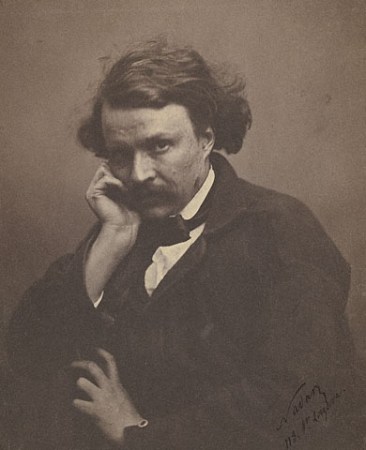

Self-Portrait (1855) – Nadar (on 4 lists)

Nadar was a newspaper caricaturist when he discovered photography in 1853 and changed careers. After two years of building a reputation, Nadar opened a studio in 1855 at 35 Boulevard des Capuchines in Paris. Nadar’s studio became the spot where artists and other well-known figures came to have their portraits made. (See 1860 photograph of Nadar’s studio below.) Nadar made numerous self-portraits, both to create a public image of himself as an artist and also to experiment with poses, lighting and other techniques. The Self-Portrait shown above dates from the time he opened his studio and probably represents an advertisement of sorts. A salted paper print of this image is in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Public domain.

Roger Fenton’s Photographic Van, Crimea (1855) – Roger Fenton (on 2 lists)

Briton Roger Fenton (1819-1869) was possibly the first war photographer. With the support of the British government, he and his assistant Marcus Sparling loaded a wagon with photographic equipment (shown above) and went to the Crimea to photograph the Crimean War between Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire against Russia. Fenton was in the Crimea from early March until late June and returned with 360 photographs. Unlike later war photos, Fenton’s images do not show battle scenes (due to the limitations of the available technology), or dead bodies (due to sensitivities of the public). Unfortunately, a lack of interest in the war among the British public led to disappointing sales and Fenton left the field of photography a few years later. A salted paper print of this image is in the collection of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855) – Roger Fenton (on 3 lists)

Of the 360 photographs British photographer Roger Fenton brought back from his four months observing the Crimean War, the most highly-regarded image showed a barren landscape – a road in a narrow, lifeless valley that is covered with spent cannonballs, a testament to the intensity of the battle fought there. Fenton apparently believed that he had photographed the site of the horrific Charge of the Light Brigade of October 25, 1854, made famous by Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s narrative poem of the same year, in which he described the battleground as “the valley of death.” When Fenton returned to England and displayed this and other Crimea photos in a public exhibit, the curators named it, in a curious amalgam of Tennyson and Psalm 23, The Valley of the Shadow of Death. In fact, the Charge of the Light Brigade happened elsewhere, but the cannonballs appeared to give proof that a fierce battle had occurred on the site. Many years later, controversy erupted over the veracity of the photograph after another of Fenton’s images surfaced showing the same scene with no cannonballs on the road (see image below). This discovery led to accusations that Fenton had manipulated the scene, particularly by documentary filmmaker Errol Morris, whose series in The New York Times can be found here:

opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one/?_r=0.

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire (1855-1858) – Nadar (on 2 lists)

French writer Charles Baudelaire, author of the classic poetry collection Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), did not believe that photography would (or should) ever rise to the status of an art. In his review of the Paris Salon of 1859, he warned that “[i]f photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether … its true duty … is to be the servant of the sciences and arts – but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature.” Baudelaire apparently saw no contradiction between his philosophical objection to photography as art and his decision to sit for his photographic portrait on multiple occasions, including seven times with French portrait master Nadar. This seated portrait captures Baudelaire in his mid-30s, confident and still youthful. A gelatin silver print is in the collection of the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York. Public domain.

Portrait of Gustave Doré (c. 1855-1859) – Nadar (on 3 lists)

Gustave Doré was a French artist best known for his wood engraved prints and book illustrations. Nadar made several photographic portraits of Doré, including the above photogravure, made when the subject was in his 20s, about the time Doré received a commission to illustrate the works of Lord Byron. As noted by a curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, “Nadar has captured the spontaneity and energy of a young artist on the rise.” Nadar, the most well-known photographer of his day, made the photograph during the early years of his career, shortly after opening his studio at 25 Boulevard des Capucines in 1855. Nadar achieved popular fame in 1858 when he took the first aerial photos from the basket of a hot-air balloon. A print of this image is in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Two Ways of Life (1857) – Oscar Gustave Rejlander (on 6 lists)

Born in Sweden, Oscar Gustave Rejlander (1813-1875) spent most of his career in France and England. After starting as a painter, Rejlander switched to photography, and became known for allegorical, painting-like photos that often combined more than one image. He was an early proponent of the artistic style that became known as pictorialism. Rejlander stumbled onto his trademark technique of combination photography when, as a novice photographer, he had difficulty keeping all the elements of the composition in focus, and so decided to make a separate negative for each element and then combine the negatives and print them together in a complicated process of photomontage. Two Ways of Life was Rejlander’s best known work. Using a composition that relies heavily on Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, Rejlander depicts a father (or a sage) showing two young brothers a choice between two lifestyles: Virtue on the right and Vice on the left. Perhaps unintentionally, the brother on the side of Vice, with its nude women and lascivious behavior, seems more engaged than the brother presented with the more refined pleasures of Virtue. What appears to be a single scene is actually a seamless montage of 32 separate negatives, a process that allowed Rejlander to reassure his proper Victorian audience that the nude women and the men were never in the same room together. The nudity was controversial nonetheless, and one museum exhibited Two Ways of Life with a curtain over the left side. Much of the criticism subsided after Queen Victoria purchased one of the few prints as a gift for Prince Albert. A silver gelatin print is in the Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum Bradford, UK. Public domain.

Fading Away (1858) – Henry Peach Robinson (on 5 lists)

A student of Oscar Gustave Rejlander, British pictorialist photographer Henry Peach Robinson (1830-1901) combined five different negatives to create a single print of the fictional deathbed scene he called Fading Away. The storytelling quality of the photo and the deep sentiment it aroused made it a bestseller for Robinson, who exhibited it at no fewer than five exhibitions in 1858-1859. But the subject matter – a young girl dying of tuberculosis – and the artificiality of the technique raised some criticisms, particularly from those who thought death was not a proper subject for photography. As with Two Ways of Life (above), the royal family once again saved the day: Prince Albert purchased a copy of Fading Away and issued a standing order for every subsequent composite photo by Robinson. An albumen print of the image is in the collection of the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, NY. Public domain.

Young Woman in Profile (c. 1859) – Nadar (on 2 lists)

Many of the surviving portraits by French photographer Nadar have no identifying information associated with them, and the viewer is left to guess at the life and circumstances of the individuals whose names are lost to history. In making this portrait of a striking young woman, Nadar softened her features by keeping the lens slightly out of focus, and turned her head so that her face is nearly in full profile to emphasize the classic outline of her forehead, nose, mouth and chin. The woman’s dark clothing and hair frame her light face and neck, which are the focal points to which our eyes are drawn. Nadar’s expert control of light and shadow gives us a sense of the delicacy and fluidity of the woman’s pale skin, softening her strong facial features. Despite the simple elegance revealed in this luminous portrait, Nadar believed the photographic process was not flattering to women’s beauty and he preferred photographing men. In fact, of the many surviving Nadar prints, only a dozen or so are photographs of women. A salted paper print of the image is located in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris. Public domain.

The Ascent of Mont Blanc (series) (1861) – Auguste-Rosalie Bisson (on 3 lists)

In the summer of 1860, French photographer Auguste-Rosalie Bisson (1826-1900) and his older brother Louis-Auguste led a photographic expedition to Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, but failed to reach the summit. The next summer, Auguste-Rosalie Bisson tried again, this time with an experienced guide and a large crew to carry all the photographic equipment. On July 25, 1861, Bisson reached the top of the 15,781-foot peak and exposed three negatives of the view. On the way down, he decided to reenact the ascent in order to photograph it. Using the wet plate collodion process, Bisson took a number of striking photographs of his crew looking like ants surrounded by giant masses of snow (see photos above and below). Albumen prints from the glass negatives are located in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Public domain. Note: Some sources state that the photograph above was taken on the 1860 trip.

Tartan Ribbon (1861) – James Clerk Maxwell and Thomas Sutton (on 5 lists)

James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), a Scottish scientist best known for his discovery that light, electricity and magnetism are all forms of the same energy, was also fascinated by the nature of color and in 1861 produced what is believed to be the first color photograph. Working with photographer Thomas Sutton (1819-1875), Maxwell photographed the Tartan Ribbon (a Scottish emblem) three times, each time with a different color filter (red, green and blue). Maxwell and Sutton then developed the three images and projected them onto a screen with three different projectors, each with the same color filter used to take the picture. When brought into focus, the three images formed a full color image. Maxwell presented his discovery as an illustration for a lecture on color he gave at the Royal Institution in London. The Maxwell-Sutton separation process became the basis for most subsequent color photography. The original three plates are now located in a museum in the house where Maxwell was born in Edinburgh. Public domain.

The Catacombs of Paris (series) (1861-1862) – Nadar (on 3 lists)

It was a de rigueur rite of passage for fashionable Parisians to venture beneath the city and explore its dark, skeleton-filled catacombs, a series of underground tunnels, formerly quarries, that had become the repository of the dead. Nadar, who had pioneered aerial photography in the 1850s using hot-air balloons, now sought to capture images in the darkest places imaginable. The result is a series of images, entitled The Catacombs of Paris, that may be the first artificially-illuminated photographs. Using a battery-operated flash lamp, a magnesium arc lamp and very long exposure times, Nadar photographed the skeletons (see photo below) and the men who worked in the catacombs. Unhappy with images of humans, who could not stand still long enough to avoid blurriness, Nadar used mannequins to stand in for the workers (see photo above). Public domain.

Civil War Battlefield, Antietam (1862) – Alexander Gardner (on 2 lists)

The Battle of Antietam, with 23,000 casualties, was one of the bloodiest in the American Civil War. Fought on September 17, 1862 in Antietam, Maryland, it was not a decisive Union victory, but it was enough to send Confederate General Robert E. Lee back to Virginia. Historians now believe that it was the Union win at the Battle of Antietam that gave Lincoln the political capital to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and convinced the European powers to stay out of this American dispute. The photograph here shows the bodies of Confederate soldiers lying on the battlefield at Antietam, next to an artillery gun on the east side of the Hagerstown Pike, with the Dunker Church in the background. This and many other Civil War photographs have long been attributed to American photographer Matthew Brady, but most of the photographs attributed to Brady were actually taken by others working in his studio. Here, the photographer working under the Brady name was Scottish-born Alexander Gardner (1821-1882), who arrived at Antietam just two days after the battle ended. There is another, very similar photograph of the same scene, also attributed to Gardner, in which the Dunker Church appears farther away than in the photo above, there is no horse by the church and the bodies seem to be spread out more neatly on the ground (see below). Public domain.

President Lincoln on the Battlefield at Antietam (Oct. 4, 1862) – Alexander Gardner (on 3 lists)

On October 4, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln visited the battlefield at Antietam, bringing General McClernand (shown at right) and Allan Pinkerton, Chief of the Secret Service. During the visit, Lincoln also met with his general (and nemesis) General Robert McClellan (see photos below). There to take the pictures was Alexander Gardner, from Matthew Brady’s studio. Although Gardner’s shots of Lincoln at the front, with soldiers’ dirty laundry hanging on the trees, were good for morale back home in the North, it was his photos of the Antietam dead that most deeply moved those who saw them.

A Harvest of Death (1863) – Timothy O’Sullivan (on 11 lists)

The Battle of Gettysburg, a turning point in the American Civil War, raged from July 1-3, 1863. Just two days later, photographers Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan (c. 1840-1882) arrived at battlefields that were still covered with the bodies of dead soldiers. Irish-born O’Sullivan had left Matthew Brady’s studio to work for Scottish-born Gardner, another Brady alumnus. O’Sullivan’s photo A Harvest of Death, taken July 5 or 6, became one of over 50 images reproduced in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866). We see Union and Confederate dead lying as they fell, with missing shoes and rifled pockets a sign that survivors had already come and taken anything they could make use of. The bloating of the corpses in the July sun has caused buttons to pop and clothing to open. Gardner’s original caption stated, in part, “It was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death’ … Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.” O’Sullivan used the collodion wet plate process, which by then had mostly replaced daugerreotypes, and Gardner made an albumen silver print for use in the Sketch Book. Public domain.

Portrait of Georges Sand (1864) – Nadar (on 5 lists)

French portrait photographer Nadar took this photograph of prolific French writer George Sand (born Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin) in 1864, when she was 60 years old. Sand was known for pushing the boundaries of gender identity by smoking and dressing in men’s clothes. Her affair with Frederic Chopin was legendary. The photograph was made using the newly invented woodburytype process, which was used to create prints for publication between 1864 and 1910, when the halftone process arrived. Public domain.

Paul and Virginia (c. 1864) – Julia Margaret Cameron (on 2 lists)

Unlike music, painting, sculpture, film and many other arts, which have been dominated by men until very recently, women have been an integral part of the growth of the photographic art since very early in the history of the medium. One of the first of these pioneering women photographers was Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). Born into a well-off English family living in Calcutta, India, Cameron moved to Great Britain and settled on the Isle of Wight, where she became associated with Victorian England’s artistic and intellectual circles. She did not begin her career as a photographer until 1863 when, at the age of 48, she received a camera as a gift. Cameron made up for lost time by photographing family members and famous and non-famous friends for the next decade of her life. To the dismay of some of her colleagues, Cameron eschewed hyper-realism and sharp focus, preferring instead to create dreamy, soft-focus portraits that hinted at the essence within instead of celebrating exterior detail. Cameron liked to dress up her subjects as characters from legend, history or fiction to add another layer of unreality to her art. In this wet collodion photograph, she dressed up two children – Freddie Gould and Elizabeth Keown – as the protagonists of the popular 1787 French romantic novel Paul et Virginie, which takes place in the South Seas. An albumen silver print of the image is in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California. Public domain.

Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt (1865) – Nadar (on 7 lists)

The renowned actress Sarah Bernhardt was one of the most-photographed subjects of Nadar, Paris’s premier portraitist in the latter half of the 19th Century. The photo above comes from an 1865 portrait session, in which Nadar dressed the 23-year-old Bernhardt in classical robes, leaning on a column, suggesting that she transcends time and belongs to the ages. He manages to show his subject’s youthful beauty while giving her a timeless look, bringing out her theatrical essence, but also the vulnerability of a young woman near the beginning of what would be a long career. For a contrasting look, see Nadar’s more contemporary portrait of Bernhardt from one year earlier, where he wraps her in dark velvet and turns her head away from the camera. An albumen print of the portrait is in the collection of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. Public domain.

Yosemite Valley from the Best General View (1866) – Carleton Watkins (on 5 lists)

On several occasions, American photographer Carleton Watkins (1829-1916) traveled from his San Francisco, California studio to photograph the remote and little-explored Yosemite Valley. Watkins carried nearly 2000 pounds of equipment by mule train, including two cameras: one that made stereographs (double shots for viewing in stereoscopes) and the other, a custom-built ‘mammoth’ camera that held glass plate negatives measuring 18 by 22 inches. The photos resulting from Watkins’ first Yosemite trek in 1861 were made into a limited edition book, a copy of which made its way to the desk of President Abraham Lincoln and likely influenced his decision to set aside the valley as the first protected public land in the U.S. in 1864. On a return trip in 1866, Watkins captured this iconic image, which takes in Yosemite Falls (in the center), Bridal Veil Falls, Half Dome, El Capitan and Cathedral Rock. Using a foreground object (here, the tall tree) to contrast with a majestic background was a trademark Watkins technique that would be adopted by subsequent landscape photographers. An albumen print is in the collection of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Portrait of Sir John Herschel (1867) – Julia Margaret Cameron (on 4 lists)

In 1867, Sir John Herschel – son of astronomer William Herschel – was an illustrious scientist and photography innovator in his twilight years. Like many of Julia Margaret Cameron’s subjects, he was also a good friend and a member of the artistic and intellectual circles that often congregated at Dimbola Lodge, Cameron’s home on the Isle of Wight. In this and other portraits, Cameron rejected the tropes of traditional portraiture. Instead of cluttering the background with faux classical columns, books, or symbols of the subject’s profession, or dressing her subjects in the robes of antiquity, Cameron chose to arrange the lighting carefully (here, from the right side) and use emotional truth as a guide for focus and pose, avoiding perfect sharpness that, in her view, accentuated every detail at the expense of the whole. The result is a Gestalt instead of a collection of attributes; it is a truly human portrait – no distractions and full of life. An albumen silver print from a glass negative is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Public domain.

Cape Horn, Columbia River, Oregon (1867) – Carleton Watkins (on 2 lists)

In the 1860s, photographic technology was still in its infancy and the size of a print was restricted by the size of the negative; it would be years before photographers could make an enlarged print from a smaller negative. It was this size restriction that led American photographer Carlton Watkins to invent the mammoth camera, which could accommodate 18 X 22 inch glass plate negatives. Watkins was convinced that only the gigantic prints he could produce from these negatives accurately represented the majesty and grandeur of the American West’s monumental landscapes. The success of Watkins’ photos of California’s Yosemite Valley in 1861 and 1866 in influencing American government policy proved him correct. In 1867, Watkins trekked by mule train north from his San Francisco home into Oregon – at the time not accessible by rail – to photograph the stunning landscapes along the Columbia River in in the new state of Oregon. (Oregon became a territory in 1848 and a state in 1859; Washington Territory was separated from Oregon in 1853, using the Columbia River as a boundary, but Washington did not achieve statehood until 1889). The wet collodion process that Watkins used required him to develop the photographs soon after exposure, so he traveled with a mobile darkroom. This view was taken from what is now the Washington side of the Columbia and shows a boat at the edge of a perfectly still river surface. Albumen prints from wet-collodion negatives are in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Public domain.

Communards in their Coffins (1871) – André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (on 4 lists)

Also known by the more prosaic title Dead Communards, this image depicts 12 men who had participated in the failed 1871 Paris Commune uprising, were arrested and executed, then placed in shabby wooden coffins and unmercifully photographed. Each one has a number placed on his chest, but there is no reason or rhyme to this apparent attempt at efficiency (two ‘4’s, no ’12’?). It is not clear whether French photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889) is seeking merely to document the dead, perhaps at the government’s behest, or whether he intends some political commentary about the cruelty of those who put down the revolt or the price one pays for rebellion. Disdéri was best known as the person who patented the mass production of the carte de visite, a small self-portrait mounted on thick paper and used as a calling card. An example of an uncut print from 1860 containing eight cartes de visite of an anonymous woman is shown below. An albumen print of Communards in their Coffins is in the Gernshein Collection, Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. Public domain.

Hot Springs on the Gardiner River, Upper Basin (stereograph) (1871) – William Henry Jackson (on 3 lists)

When Ferdinand Hayden was organizing a U.S. Geological Survey expedition to Wyoming, he selected American William Henry Jackson (1843-1942) as his team photographer, thus giving Jackson the opportunity to be one of the first to capture the wonders of Yellowstone through the relatively new medium. The double print above, known as a stereograph, is designed for use in a stereoscope (see image below), which created the illusion of three-dimensionality, similar to the 20th Century View-Master (for those old enough to recall). The stereograph shows duplicate images of the terraces of the Mammoth Hot Springs on the Gardiner River in Wyoming in what is now Yellowstone Park. The man with his back to the camera is probably Thomas Moran, the staff artist. Jackson’s photos and Moran’s sketches and paintings were important factors in the federal government’s decision to make Yellowstone the nation’s first national park in 1872.

Ancient Ruins in the Canyon de Chelly (1873) – Timothy O’Sullivan (on 4 lists)

In the 1870s, Timothy O’Sullivan obtained a position as photographer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers survey of the Western U.S. led by George Montague Wheeler and lasting from 1872-1879. The ruins in the photograph, known as the White House, are located in Canyon de Chelly in what was then New Mexico Territory and is now Arizona. The White House is the remains of an Anasazi cliff dwelling built and inhabited between 1100-1300, when the Anasazi people left the area. Canyon de Chelly is part of the Navajo Nation as well as a National Monument. In his photograph, O’Sullivan emphasizes the vast striated cliffs, which dwarf the ruins and serve as a substitute sky. The most famous photograph taken in Canyon de Chelly is a 1904 image by Edward Curtis showing seven Navajo riders (see below). Albumen print. Public domain.

Mount of the Holy Cross (1873) – William Henry Jackson (on 5 lists)

In 1873, American photographer William Henry Jackson went to Colorado to find a legendary mountain that displayed a cross of snow. Jackson found the Mount of the Holy Cross in the high Rockies in the Sawatch Range – it was late summer and just enough snow had melted to allow the snow remaining in crossing ravines to create the shape of a Christian cross on the mountain’s northeast face. Jackson climbed up another mountain to get the best angle and the early morning light and took eight photographs, the best of which is shown above. The photo confirmed the legend. Over the years, Jackson returned to the spot in an attempt to duplicate the image, without success. Public domain.

No. 27, Once a little vagrant; No. 28, Now a little workman (c. 1875) – Thomas John Barnardo & Thomas Barnes (on 3 lists)

Thomas John Barnardo (1845-1905) was an Irish philanthropist who founded 112 homes for homeless children in England between 1870 and his death in 1905. In 1874, Barnardo began photographing each child upon arrival and then several months later to show the improvements brought on by education, nutritious food, loving care and the gainful use of their time. Barnardo hired East End photographer Thomas Barnes to make these ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs, which were sold in sets as a way to publicize the charity and also to raise funds. One such pair of photos is shown above: No. 27, Once a Little Vagrant and No. 28, Now a Little Workman focuses on the worst fears and best hopes of the average citizen: the shiftless homeless child, likely as not to steal your purse, has been transformed by Dr. Barnardo into an industrious cobbler’s apprentice, who will benefit society instead of preying upon it.

The Crawlers (from Street Life in London) (1877) – John Thomson (on 3 lists)

After many years of travel in the Far East, British photographer John Thomson (1837-1921) settled in London where in 1876 he embarked on a collaborative project with journalist Adolphe Smith. Together, they published a monthly magazine called Street Life in London, in which Thomson’s photos (made using the woodburytype process) and Smith’s text documented the lives of the city’s desperate poor. The magazine ran from 1876-1877, after which Thomson and Smith published a book of the same name in 1878. In the most well-known of the Street Life photos, an older woman sits on the steps of a workhouse, caring for the child of a woman who has managed to find some work. In return, the woman received some scraps of food. She and others were called crawlers because they no longer had the strength to beg. Public domain.

The Horse in Motion (series) (1878) – Eadweard Muybridge (on 10 lists) X

In 1872, prominent California politician and businessman Leland Stanford asked English-born photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) to settle a question that had perplexed both experts and the public for years: Did all four of a running horse’s legs ever leave the ground at the same time? (The legend that there was a large sum of money riding on the outcome is probably false: https://alumni.stanford.edu/get/page/magazine/article/?article_id=39117.) The horse’s legs moved too quickly for human eyes to see, but Muybridge convinced Stanford that he could answer the question with photography. Muybridge initially experimented with a single camera using very short shutter speeds to photograph the horse Occident in 1872, 1873, and 1877. This resulted in one grainy photograph that showed all four feet off the ground but retouching of the negative led experts to regard the resulting published print as a manipulated fake. In 1878, Muybridge tried a different approach. He set up 12 closely-spaced cameras along a racetrack with wires that the horse’s legs would trip, causing each camera to make an exposure of approximately 1/500 of a second. With the press watching on June 15, 1878, trainer Charles Marvin ran the trotter Abe Edgington around the track at a 2:24 gait. Muybridge quickly developed the film, which showed all four legs off the ground in the ninth frame of the series, and presented it to the gathered crowd (see images below). During the next few days, Muybridge had several different horses run the track at different paces – trotting, cantering and galloping. Later in the same year, he published The Horse in Motion, a set of six photographic cards that included the 12 photos from the original Abe Edgington run as well along with two other trots by the same horse on June 18 (one with eight frames and one with six frames), a trot by Occident, a canter by Mahomet on June 17 (six frames) and a gallop at a gait of 1:40 by thoroughbred Sallie Gardner on June 19 (12 frames). Sallie Gardner (see image above) became the most well-known of the six-pack of cards, perhaps because the second frame of the series illustrates the “flying horse” pose much better than the photographs of the trotters. Soon after the success of The Horse in Motion, Muybridge doubled the number of cameras, resulting in even more detailed information about motion. Engravings of Muybridge’s series made it into newspapers and the front page of Scientific American magazine. Muybridge also converted the photos into silhouettes and then ran them in a zoopraxiscope to create an animated ‘movie’ of the horse galloping, one of the earliest precursors of motion pictures.

Birds (1879) – Louis Ducos du Hauron (on 2 lists)

After Maxwell and Sutton’s early experiments, the next important innovator in the field of color photography was French physicist Louis Ducos du Hauron (1837-1920), who invented and obtained a patent for a new color technique called the trichrome process. Trichrome photography required Ducos du Hauron to take photographs of the subject using three different filters tinted green, orange and violet. He then printed the three negatives on transparent sheets of bichromated gelatin containing carbon pigments in the complementary colors of red, blue and yellow. When all three transparencies were superimposed, the result was a full color photograph. The color photograph shown above is known variously as Birds, Mounted Birds, Still Life with Rooster and Still Life with Rooster and Parakeet. As is so often the case with scientific discoveries, at almost the same time that Ducos du Hauron was inventing the trichrome process, another French scientist, Charles Cros, arrived at the same result, although he was 48 hours too late to claim the patent. A print of Birds is in the collection of the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, NY. Public domain.

Storks (series) (1884) – Ottomar Anschutz (on 3 lists)

German photographer Ottomar Anschütz (1846-1907) was interested in capturing objects and beings in motion, so he invented a camera that could take sharply-focused pictures of momentary events using a shutter speed of 1/1000 of a second. Using his unique equipment, he produced a famous series of pictures of Storks (also known as Storks in Flight) that would prove to be an inspiration for Otto Lilienthal’s later experiments with gliders. Albumen prints may be found in the collection of the Otto Lilienthal Museum in Anklam, Germany. Gelatin silver prints are located at Western Michigan University and the University of Michigan.

The Art of Living a Hundred Years (series) (1886) – Paul Nadar (on 3 lists)

The September 8, 1886 edition of Le Journal illustré, a Paris newspaper, contained an extensive interview with 100-year-old French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul conducted by Nadar, the famous French photographer. Accompanying the article, which was titled The Art of Living 100 Years, were 13 halftone prints of Chevreul, both alone and with Nadar, using photographs taken by Nadar’s son Paul (1856-1939). The resulting article is considered the first photo-interview, a blending of photographs and text that was made possible by the recent invention of the halftone process. Gelatin silver prints are in the collection of the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

An Ancient Lodger and the Plank on Which She Slept, at Eldridge Police Station (c. 1888-1890) – Jacob A. Riis (on 3 lists)

Born in Denmark, Jacob Riis (1849-1914) came to New York and became a journalist. In 1878, he obtained a prime position as a police-beat reporter for the New York Tribune, covering the notorious slum neighborhood of Mulberry Bend. He documented the squalor and misery of the tenement dwellers and the homeless in newspaper articles and lectures, all of which were designed to bring about social reform. In 1888, Riis began supplementing his articles and lectures with photographs: he used glass-plate negatives and the recently-invented magnesium flash to pierce the dark tenements, alleys and hideouts that so often featured in his stories. For ten years, Riis made images of searing power, and then, satisfied that he had enough documentation, he put down his camera. This image, with an unexplained hand entering from the right, is part of a series of photos of indigent men and women who lodged at the de facto homeless shelters set up at various police stations. Riis was convinced that these police lodging houses were breeding grounds for crime and disease. A gelatin silver print of this image is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. An albumen print is in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

The Onion Field (1889) – George Davison (on 3 lists)

The Onion Field is the most highly-regarded photograph by British photographer George Davison (1854-1930). After experimenting with techniques that rendered sharp, realistic images of landscapes, Davison opted instead for the hazy impressionism that would become the hallmark of pictorialism. The Onion Field was made with a pinhole camera and printed on rough paper to create the impression of a painting. Davison’s pictorialist views found no favor in the Royal Photographic Society, so he left that organization and founded his own, the Linked Ring Brotherhood. Years later, Alfred Stiegliz paid tribute to Davison by publishing the image in 1907 in Camera Work with the title An Old Farmstead. Raised in poverty as the son of a shipyard carpenter, Davison obtained employment at Eastman Kodak UK in 1888 and eventually became a millionaire.

The Photographer’s Wife (1890) – Nadar (on 2 lists)

Ernestine, the wife of French photography innovator Nadar, was the subject of many of his photographs during their 54 years together, but no other portrait has the impact of this 1890 image, taken in 1890, when the couple had been married 36 years, Ernestine was 54 years old and Nadar, having retired professionally in 1873, was 70. In The Photographer’s Wife, Ernestine holds a flower to her mouth – to kiss it? to stifle her own voice? – while her penetrating eyes gaze back at the man she has chosen to spend her life with – searching, critiquing, and accepting him all at once. In his book Camera Lucida, art theorist Roland Barthes called The Photographer’s Wife “one of the loveliest photographs in the world.”

Chronophotographic Study of Man Pole Vaulting (1890-1891) – Étienne-Jules Marey (on 3 lists)

Étienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904) was a French physician who became fascinated by animal movement and became a pioneer in the fields of both photography and cinema. Beginning in the 1870s, he began experimenting with cameras that could create multiple exposures within a single frame, thus allowing a scientific study of motion. After early work with birds and a famous series showing how a cat always lands on its feet, Marey turned to human beings. In 1882, he developed a chronophotographic camera that could take 12 photographs per second and expose them all on a single negative. On at least two occasions, he aimed the camera’s gun-like barrel at a man performing a pole vault. An earlier version dates to 1886-1887, while the above image (or images) dates to 1890-1891. Like Harold Edgerton’s strobe-flash photos, Marey’s scientifically-titled Chronophotographic Study also has much artistic beauty in it.

The Terminal, New York (1892) – Alfred Stieglitz (on 4 lists)

American photography innovator Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) – who campaigned his entire career to promote the young medium as a serious art form – had recently returned from several years in Europe in 1892 when he found himself in front of the New York City Post Office where two different streetcar lines terminated. The winter scene of steaming horses and their drivers restIng at the end of the line expressed Stieglitz’s sense of being a stranger in his hometown. Stylistically, The Terminal shares much with pictorialism, but the candid urban setting (and Stieglitz’s use of a 4 X 5 camera, which was much more mobile than the usual tripod-bound 8 X 10) prefigure the straight photography movement of the 20th Century. Public domain.

A Venetian Canal (1894) – Alfred Stieglitz (on 2 lists)

Photography-as-art booster Alfred Stieglitz took the photograph A Venetian Canal on his 1894 honeymoon, and he admired it so much that he published it at least three different times: in Camera Notes magazine in 1897; in The Photographic Times in 1898 and in his book Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies (1897) (under the title A Bit of Venice). A Venetian Canal was also included in the Camera Club of New York’s 1899 portfolio. A contemporary reviewer thought the photograph “gives a better idea of Venice than many a painting.” (Sadakichi Hartmann, “An Art Critic’s Estimate of Alfred Stieglitz”, The Photographic Times: June, 1898.) An 1898 print from the original negative is in the collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio. Public domain.

Denver, Colorado (panorama) (1898) – William Henry Jackson (on 2 lists)

Born in Keesville, New York in 1843, William Henry Jackson moved to Omaha, Nebraska in 1867 and began a long career as one of the foremost photographers of the American West. After photographing the building of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1867-1869 and capturing Yellowstone during the Hayden Survey, Jackson moved to Denver, Colorado and in 1879, established a studio there. Denver remained his home base until 1898, when he relocated to Detroit, Michigan. His 1898 color panoramic photograph of Denver was taken from the top of the state Capitol building, looking northwest down 16th Street, with the intersection of 16th Street and Broadway in the foreground. The domed building on the left side is the Arapahoe County Courthouse, which was demolished in 1933. The Brown Palace Hotel is visible on the right. Public domain.

Blessed Art Thou Among Women (1899) – Gertrude Käsebier (on 2 lists)

Influential American photographer Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934), the first woman to be accepted in the New York circle that included Alfred Steiglitz, Edward Steichen and Paul Strand, was a dedicated practitioner of pictorialism, which aspired to make photography a high art by using soft focus and other painterly effects and by addressing profound themes and subjects. Blessed Art Thou Among Women – a double portrait of Agnes Lee and her daughter Peggy (Agnes, a poet, was married to amateur Boston photographer Francis Watts Lee) – is a masterpiece of the style. The ethereal white-clad mother becomes almost one with the white door frame as she leans over to create a tender arch at the threshold where the young girl – her dark clothing drawing our gaze – is ready to step out into the world. The intimacy of this mother-daughter moment is made universal by the painting on the wall of the Annunciation, during which the Angel spoke the title’s words to Mary in announcing that she would be the virgin mother of Jesus. A 1907 reviewer praised “the utmost reach of tender maternity, the affection that is of renunciation and self-control rather than demonstration.” (Giles Edgerton, “Photography As An Emotional Art: A Study of the Work of Gertrude Käsebier,” The Craftsman, vol. 12 (April 1907): 92.) A platinum print is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Brooklyn Museum of Art possesses a photogravure of the image. Public domain.

The Red Man (c. 1899) – Gertrude Käsebier (on 2 lists)

Alfred Stieglitz published The Red Man, Gertrude Käsebier’s moody portrait of a Native American, in the very first edition of his new magazine Camera Work in January 1903. The portrait embodies the principles of pictorialism: “refined compositions with soft-focus effects and low tonalities.”(http://www.artsconnected.org/resource/15013/1/the-red-man.) Käsebier became fascinated with Native Americans and their culture after seeing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show when it visited New York City in 1898-1899. Many of the cast members visited Käsebier in her studio to have their portraits taken, including Takes Enemy, the Sioux Nation member depicted in The Red Man. The fortuitous survival of the original negative from this session (shown below) demonstrates the extent to which the photographer manipulated the image in the darkroom (another key aspect pictorialism, which held that straight, realistic photographs were not art). A photogravure of The Red Man is in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in Minnesota. Public domain.

Lampshade Peddler (1899-1900) – Eugène Atget (on 2 lists)

Eugène Atget (1857-1927) was a French documentary photographer known for his photos of Parisian street scenes and architecture. Beginning around 1897, Atget dedicated himself to documenting what remained of the Paris of old before it was lost or destroyed. American photographer Berenice Abbott met Atget in Paris in the 1920s while she was working for Man Ray and she became a friend, booster and ultimately preserver of his work. When Atget died, Abbott bought his negatives and in 1956, she produced a book containing 20 photographs, including this portrait of a Parisian Lampshade Peddler at the turn of the century. In his portraits of Paris tradesmen and women and others, Atget drew upon his experience in theater. Critic James Borcoman points out that the background in Lampshade Peddler and other portraits “slopes upward and into the distance in the manner of the exaggerated perspective of stage scenery.” Eugene Atget, 1857-1927 (National Gallery of Canada, 1984). A toned gelatin silver print is in the collection of the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, Calfornia. Public domain.

Versailles Parc (1901) – Eugène Atget (on 2 lists)

French photographer Eugène Atget did not think of himself as an artist but as a collector of images, or “documents for artists.” But history has revealed that Atget’s photographs of Paris and its environs contain a deep level of craft and artistry. For example, Atget’s photos of the parks and gardens of Versailles transform what could otherwise have been banal tourist snapshots into a celebration of the “combination of elegance, order and baroque excess” that “embodied the essence of French civilization”, in the words of the curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In Versailles Parc, Atget has used the light sensitivity of the albumen printing process to underexpose the vast dark mass of foliage, while at the same time overexposing the sky and light dirt path, leaving us with almost abstract patches of dark and light to frame the points of interest – the man-made statue and bench. Versailles became a touchstone for Atget in his last years as he struggled to document the beauty of the French past. The National Gallery of Canada has a matte albumen silver print of the image in its collection. Public domain.

Rodin and The Thinker (1902) – Edward Steichen (on 2 lists)

Luxembourg-born photographer Edward Steichen (1879-1973) came to the U.S. as a young man and came to be closely linked with Alfred Steiglitz as a proponent of pictorialism. Later, Steichen became famous for his Hollywood portraits. As a cap on a brilliant career, he influenced the course of the medium he loved as curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art from 1947-1961. In 1902, during his pictorialist phase, Steichen traveled to France to meet Auguste Rodin and make a portrait of the man considered the greatest living sculptor. Steichen visited Rodin every week for a year – getting to know the man, his studio and his working methods – before making the green-tinted portrait shown above, which embodies the quintessence of the pictorialist style. Steichen wanted to show Rodin in profile facing the bronze Thinker, with the marble Monument to Victor Hugo behind them. Unfortunately, the two statues were placed too far apart in the crowded studio to permit such a composition. Instead, Steichen produced two negatives – one of Rodin and The Thinker, the other of the Victor Hugo, and combined them in the darkroom to create the composite shown above, with the dark figures silhouetted against the massive marble monument. Crucial to Steichen’s vision – and the pictorialist philosophy – is his rendering of the surfaces of the bronze and marble statues so that they lose their particular characteristics and blend instead into a soft-focus texture that harmonizes with the figure of the artist himself. Steichen eliminates any element that would destroy the illusion that these are three animate beings united in the pursuit of high art. Gum bichromate prints of Rodin and the Thinker (also known as Rodin-The Thinker) are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Musée Rodin in Meudon, France. A photogravure is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Public domain.

Portrait of Miss N (Evelyn Nesbit) (1902) – Gertrude Käsebier (on 3 lists)

As photographer and subject, Gertrude Käsebier and Evelyn Nesbit could not have been more different: Käsebier was a mother of three, married to a man she did not love, who had decided to go to art school at the age of 37 and become a professional photographer. At 18, Evelyn Nesbit was already a notorious celebrity: a fashion model and stage actress who had been associated with numerous men, especially architect Stanford White, who began his relationship with Nesbit when she was 16 and he was 47. Years after this photo was taken, Nesbit’s unstable millionaire husband would shoot and kill Stanford White in a restaurant. Käsebier was the first woman in Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession group, and she was considered the best portraitist of her day. She adhered to the dominant pictorialist style, which emphasized hazy painting-like effects and composition over harshly etched realism. Portrait of Miss N. is lucid enough to create a useful likeness of this turn-of-the-century ‘It’ girl, but the composition (particularly the gesture of offering the pitcher) and the gauzy overlay place the photography squarely within the pictorialist tradition. Ironically, after becoming one of the first women to be accepted by her male cohorts, Käsebier split from Stieglitz and others over the issue of commercialism. With three mouths to feed, and a chronically ill husband, Käsebier found the Photo Secession’s ‘art for art’s sake’ philosophy a luxury she could not afford. Public domain.

The Wright Brothers’ First Flight, North Carolina (Dec. 17, 1903) – John T. Daniels, Jr. (on 3 lists)

Although he took one of the most famous photographs in history, John T. Daniels, Jr. (1873-1948) was not a photographer. Daniels was a member of the Kill Devil Hills Lifesaving Station in North Carolina, which was run by the U.S. Coast Guard. He and other members of the station assisted and witnessed Orville and Wilbur Wright when they made the first heavier-than-air, manned, powered flights, on December 17, 1903. The Wrights had come equipped with a Gundlach Korona view camera with a 5 X 7 inch glass-plate negative to record the event (and stave off patent disputes). They set the camera on a tripod and Orville asked Daniels – who had never seen a camera before – to squeeze the bulb when the plane was airborne. Orville won a coin toss and made the first flight, first running the plane along a monorail installed in the sand, then taking off. Daniels took the picture as the biplane was rising up and had reached an elevation of two feet. The first flight was only 12 seconds long. Other photos taken that day, including a photo of the much longer third flight, did not come out clearly. Public domain.

Flatiron Building, New York (1903) – Alfred Stieglitz (on 3 lists)

Like so many innovators, Alfred Stieglitz had a complicated relationship with his art. He is best known for his passionate crusade to have photography taken seriously as an art form. He founded the Photo-Secession and Studio 291 (with Edward Steichen) and the influential magazine Camera Work. At first, he believed that pictorialism – manipulating photos to create painting-like effects – was the artistic style, while documentary or straight photography – just pointing the camera and taking the picture – could not be defended as art. But throughout his career, Stieglitz’s work betrays a straight photographer hiding beneath the pictorialist trappings. His photo of the Flatiron Building – then a symbol of modernism – belies an interest in pure form (particularly the tree in the foreground) that would resurface in The Steerage and the work of Paul Strand. Public domain.

The Flatiron Building, New York City (1905) – Edward Steichen (on 4 lists)

One of the first skyscrapers in Manhattan, the 22-story Flatiron Building opened in 1902 and immediately became a magnet for photographers. Pictorialist photographer and Photo-Secessionist Edward Steichen chose to take his Flatiron portrait at twilight in winter, with bare tree branches and horse carriages in silhouette, to create the hazy sense of a painted canvas. Steichen experimented with color by adding dyes in the production process – he used three separate dyes, each one to reflect a different aspect of the growing darkness of twilight, to create three original prints from a single negative. Public domain.

Looking down Sacramento Street, San Francisco (April 18, 1906) – Arnold Genthe (on 5 lists)

A massive earthquake shook San Francisco at just after 5 a.m. on April 18, 1906 and almost immediately set off fires across the city. German-born photographer Arnold Genthe’s (1869-1942) studio and all the cameras in it were destroyed by falling debris, so he went to a friend’s camera shop the same morning and borrowed a 3A Kodak Special camera and lots of film and began photographing the devastation. The best known shot is one taken on Sacramento Street on Nob Hill, looking down toward the advancing fire. On the right, we see a house whose front has fallen into the street. Up and down the hill, groups of people stand or sit in chairs watching the spectacle. Public domain.

The Steerage (1907) – Alfred Stieglitz (on 12 lists)

When American photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his family traveled to Europe in a first class berth on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1907, the movement known as pictorialism had dominated photography for several decades. Pictorialists believed that photographs could become art, but only through the skillful manipulations of the artist at all stages of the photographic process. Straight photography, is it was known, was merely scientific representation of reality, with no artistic mediator. Pictorialist photos were rarely in sharp focus, and tended to have the quality of perfectly-composed paintings. Some pictorialists went even further and constructed artistic photographs by using multiple negatives. A gallery owner and magazine editor, Stieglitz was a major force behind the notion that photography could be art and was considered a pictorialist in 1907. Yet his photo of the steerage section of the Kaiser Wilhelm, with its sharp details and attention to structural lines, is anything but pictorialist. Instead, The Steerage eventually became evidence that straight photography could also be artistic. Stieglitz himself did not immediately recognize the importance of his watershed image – it was only four years later, in 1911, that he published it in one of his photography magazines. He published it again in 1913 and by 1915 devoted a whole issue of 291 magazine to The Steerage. By that time, the tide had begun to turn away from pictorialism and toward straight photography. Stieglitz’s photo is now considered both a cultural document and a work of art. Public domain.

Sadie Pfeifer. 48 inches tall. Has worked half a year. Lancaster Cotton Mills, South Carolina (1908) – Lewis Hine (on 7 lists)

As the photographer for the U.S. National Child Labor Committee, a non-profit organization dedicated to ending the practice of child labor, Lewis Hine’s (1874-1940) assignment was to capture in photographs the truth about working children in the U.S. in the early years of the 20th Century. Hines traveled all over the U.S., taking documentary-style photographs of children working in factories, mills and mines, as paperboys and in all-night bowling alleys. The photographs were instrumental in the passage of child labor laws. Here, Hine shows a young girl in a tattered dress working in a South Carolina cotton mill. Hine composes the shot so that the huge machines and factory walls dwarf the girl and her co-worker. A gelatin silver print is in the collection of the Library of Congress, which owns all the original photographs. The original photos and captions can be viewed at:

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/. Public domain.

Spinner in Whitnel Cotton Mill (1908) – Lewis Hine (on 5 lists)

Lewis Hine’s original caption for the National Child Labor Committee for this photograph read as follows: “One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She was 51 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. Sometimes works at night. Runs 4 sides – 48 [cents] a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, ‘I don’t remember,’ then added confidentially, ‘I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same.’ Out of 50 employees, there were ten children about her size. Whitnel, North Carolina.” The original is in the collection of the Library of Congress.

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/. Public domain.

Child Laborer in Newberry, South Carolina Cotton Mill (1908) – Lewis Hine (on 2 lists)

It is hard to imagine today’s public relations experts and spin doctors allowing Lewis Hine to photograph children at work in their business establishments, but security was apparently lax in the early 20th Century, and Hine (sometimes posing as an insurance inspector) was able to capture the reality that children were working long hard hours at strenuous jobs all over the US. A common ruse given to explain the presence of quite young children, such as this girl in a South Carolina cotton mill, was that they didn’t really work there but had just stopped by to see a family member. In his caption for this photo, Hine reported: “The overseer said apologetically, ‘She just happened in.’ She was working steadily. The mills seem full of youngsters who ‘just happened in’ or ‘are helping sister.’ Newberry, South Carolina.” The way the girl plasters her arms to her sides in an almost military posture is deeply touching. Library of Congress. Public domain.

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/.

One a.m. but young pin boys are working, Brooklyn, NY (1909) – Lewis Hine (on 2 lists)

Lewis Hine’s photograph shows young boys working in a Brooklyn bowling alley long after midnight, with their mustachioed boss standing watch over them. The mural on the back wall shows ships, a hint that this establishment may have been in or near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In his notes, Hine indicated that there were three even younger boys working that night, but the employer would not allow him to photograph them. Library of Congress. Public domain.

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/

Playground in Mill Village, Boston (1909) – Lewis Hine (on 4 lists)

While working for the National Child Labor Committee, Lewis Hine not only documented children at work but also at play, as in this photo of a ball game in a crowded alley between two sets of tenement apartments in Boston, beneath drying laundry. Playground in Mill Village (also known as Playground in Tenement Alley) was useful in documenting the lack of safe places for children to play and supported efforts to build playgrounds and parks in the inner cities. Library of Congress. Public domain. http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/.

Newsies at Skeeters Branch (May 9, 1910) – Lewis Hine (on 2 lists)

Lewis Hine’s most famous photograph shows young newspaper boys dressed and acting like grown men. In contrast to the many heartbreaking images in Hine’s catalog, here the humorous element predominates, although scratch the surface and we realize that these boys worked as hard as their fathers and mothers did, and so their grown-up mannerisms were ironically apt – hard labor had stolen their childhoods. Hine’s original caption: “11:00 A.M. Monday, May 9th, 1910. Newsies at Skeeter’s Branch, Jefferson near Franklin. They were all smoking. Location: St. Louis, Missouri.” A gelatin silver print is in the Library of Congress. Public domain.

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/.

Breaker Boys in Coal Chute, South Pittston, Pennsylvania (1911) – Lewis Hine (on 3 lists)

Breaker boys were used in the anthracite coal mines to separate slate rock from the coal after it had been brought out of the shaft. The boys often worked 14 to 16 hours a day. Notes taken by photographer Lewis Hine, then working for the National Child Labor Committee, indicate that this picture was taken at the noon break, although the sun shining through a rear window barely illuminates the dreary, soot-drenched interior. Hine asked the boys their ages, but they were suspicious of him and often lied, telling him they were 12 or 14 when it was clear they were much younger. This and Hine’s many other photos of children at work were instrumental in the passage of laws prohibiting child labor in the US. Library of Congress.

http://www.lewishinephotographs.com/.

The Octopus (1912) – Alvin Langdon Coburn (on 3 lists)